The Dutch National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden recently acquired a rather special set of coins.

The first find in Mainland Europe to contain both British and Roman coins, the Bunnik Hoard (named after the village on the outskirts of Utrecht where it was discovered in October 2023) has thrust this part of the Roman limes and its connections with neighbouring Britannia into the spotlight.

Besides 72 gold aurei and 288 silver denarii, Roman coins likely linked to military payments, the chance discovery by locals Reinier Koelink and Gert-Jan Messelaar also yielded 44 gold staters attributed to the pre-Roman British king Cunobelinus, a highly unusual find on this side of the North Sea.

Cunobelinus was King of the Catuvellauni, and ruled lands stretching from the River Thames eastwards into present-day Suffolk, Essex and Kent. These lands were well-placed to exploit ever increasing trade opportunities with the burgeoning empire just across the water — wine, oil, and other luxury goods — but it was a position that would soon show its downsides too.

Following Cunobelinus’s death, two of his sons played a leading part in opposing the Roman invasion under Claudius, which soon arrived at their vulnerably close shores in 43 AD.1 It is generally assumed that Aulus Plautius — the man charged with leading that initial invasion — was supported by Batavian forces hailing from the watery lands at the mouth of the Rhine, famed for their ability to swim across great rivers fully armed.2

Indeed, it is likely that the Cunobelinus coins from the Bunnik Hoard made their way across the sea as the spoils of war following that first invasion of Britain. Early analysis points to a wide chronological range for the coins, a sign that they were likely removed from circulation in a single event, rather than selectively assembled. Furthermore, the location of the find — in a soggy field far from habitation and other known Roman sites — suggests that they were deliberately deposited in one go, perhaps as a ritual offering by Batavians relieved to be safely home following their fluvial exploits across the sea.3

The Bunnik Hoard thus adds further weight to the importance of the Rhine delta and surrounding lowlands for the supply of Roman Britain. As a way to transport troops and goods from south to north relatively easy and cheaply, the Rhine was the “motorway” of Roman Europe, as one expert described it in 2005, when British TV’s Time Team were invited to help excavate a beautifully preserved Roman boat just outside Utrecht, on the opposite side of the city to the Bunnik Hoard’s find spot.

The Time Team boat was covered up again following the excavations and is now buried under a cycle path (what else in the Netherlands?!), secured for future research. A similar Roman boat is however on display at the nearby museum at Castellum Hoge Woerd. A remarkable vessel, she came complete with a lockable cabin for peace of mind when on the move with previous cargo or simply one’s personal effects.

The connection with the Low Countries would continue to stretch northwards with the empire’s frontier, as the Romans pushed ever further into Britain. At the isthmus between the Tyne and the Solway, where Hadrian would later build his famous wall, a series of early forts were established, among them Vindolanda, which was manned by the Ninth Cohort of Batavians between 90 and 105 AD.

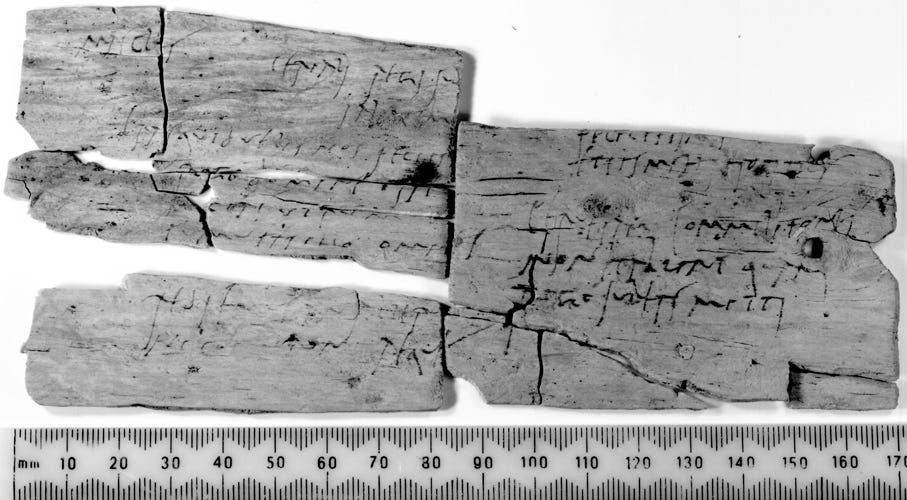

Some of the famous writing-tablets preserved from Vindolanda suggest that the Batavians stationed here brought with them food and drink preferences from home. One tablet from the Batavian period, found in a room identified as a kitchen, refers to a garlic mixture (alliatum) and spiced wine or pickling liquor (conditum), and also contains the word batauico ‘in the Batavian fashion’, though the fragmented nature of the tablet today does not allow us to know exactly what lowland regional speciality this refers to.

In another tablet, Masclus, a cavalry officer of the Batavian cohort, complains to the cohort’s prefect, Flavius Cerialis, that his fellow soldiers ‘have no beer’, and could he ‘please order some to be sent.’4 The Lower Rhine region which Masclus and his fellow Batavians knew as home was a strong beer-drinking area at the time, a habit that apparently stuck with them on their travels north.5

Besides the Batavians, so too their Frisian neighbours left traces at the northern fringes of Britannia. Handmade pottery found at Roman forts along Hadrian’s Wall — first referred to as “Housesteads Ware” after the imposing fort high on the Whin Sill crag — was later noticed to have similarities with Roman vessels from the terp settlements in today’s Friesland, Groningen and North Holland provinces.6 Analysis of the clay has since revealed that it was made in Britain, rather than being imported, most likely the work of Frisian soldiers stationed at these northern outposts, or perhaps even their wives and children.7

Plentiful traces of Batavians and Frisians on land there may be, but many questions remain open — not least as to the specific sea routes by which these peoples arrived in Britannia. While the standard view has tended to assume that most journeys from the Rhine delta crossed the sea via the Channel, scattered finds near the mouth of the Tyne suggest that maritime journeys from the Continent could also end and begin here. An inscription at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, found in 1903 while dredging the north channel of the Swing Bridge (always my personal favourite of the Quayside bridges), commemorates the arrival of troops from the Germanic provinces. And just a few miles down river at South Shields, an altar found sometime before 1672 was dedicated to the welfare of Emperor Caracalla and his son Geta on their return to the Continent, their journey said to have ended at modern-day Katwijk, at the mouth of the Rhine.8

Whatever the case, with nearly two thousand years of waves, floods and tides separating us from the time, one needs to be patient to find the few clues which still remain.

Malcolm, Todd, Cunobelinus [Cymbeline] (d. c. ad 40), king in southern Britain. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004.

M. W. C. Hassal, Batavians and the Roman Conquest of Britain. Britannia 1, 1970, pp. 131-136.

Anton Cruysheer & Tessa de Groot, The Bunnik Hoard 2023: Outline and initial analysis of the Roman coin hoard Bunnik (Utrecht, The Netherlands).

David B. Cuff, The King of the Batavians: Remarks on Tab. Vindol. III, 628. Britannia 42, 2011, pp. 145-156.

Martin Pitts, Globalisation, circulation and mass consumption in the Roman World. In Martin Pitts & Miguel John Versluys (eds.), Globalisation and the Roman world: World history, connectivity and material culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 2015), pp. 69-98.

Ian Jobey, Housesteads Ware: A Frisian tradition on Hadrian’s Wall. Archaeologia Aeliana Series 5, Vol. 7, 1979, pp. 127-143.

M. C. Galestin, Frisii and Frisiavones. Palaeohistoria 49/50, 2007/2008, pp. 687-708.

Jasper de Bruin, From The Hague to Britannia: Severan military activities along the North Sea coast (193-235 AD). In R J. van Zoolingen (ed.), AB HARENIS INCVLTIS: Artikelen voor Ab Waasdorp (Gemeente Den Haag, afdeling Archeologie, 2019), pp. 137-153.

Fantastic article. I loved reading the information about the link between Housesteadware and pottery found in Friesland and North Holland. It would be great of the Romans arrived by boat via the River Tyne too!

The gold and silver coins look in really good condition. The Bunnik hoard is a wonderful recent discovery. The Leiden Museum of Antiquities is definitely worth a return visit when I'm next in the Netherlands.

What beautiful juicy coins, I love that grain pattern!