For as long as we can tell, we humans have named the places important to us in reference to features in the landscape — below that hill there, by this meeting of rivers here, in that forest clearing through the trees.

What to do, then, when you need to name a newly discovered oil field, in the middle of the featureless blue-grey expanse of the North Sea?

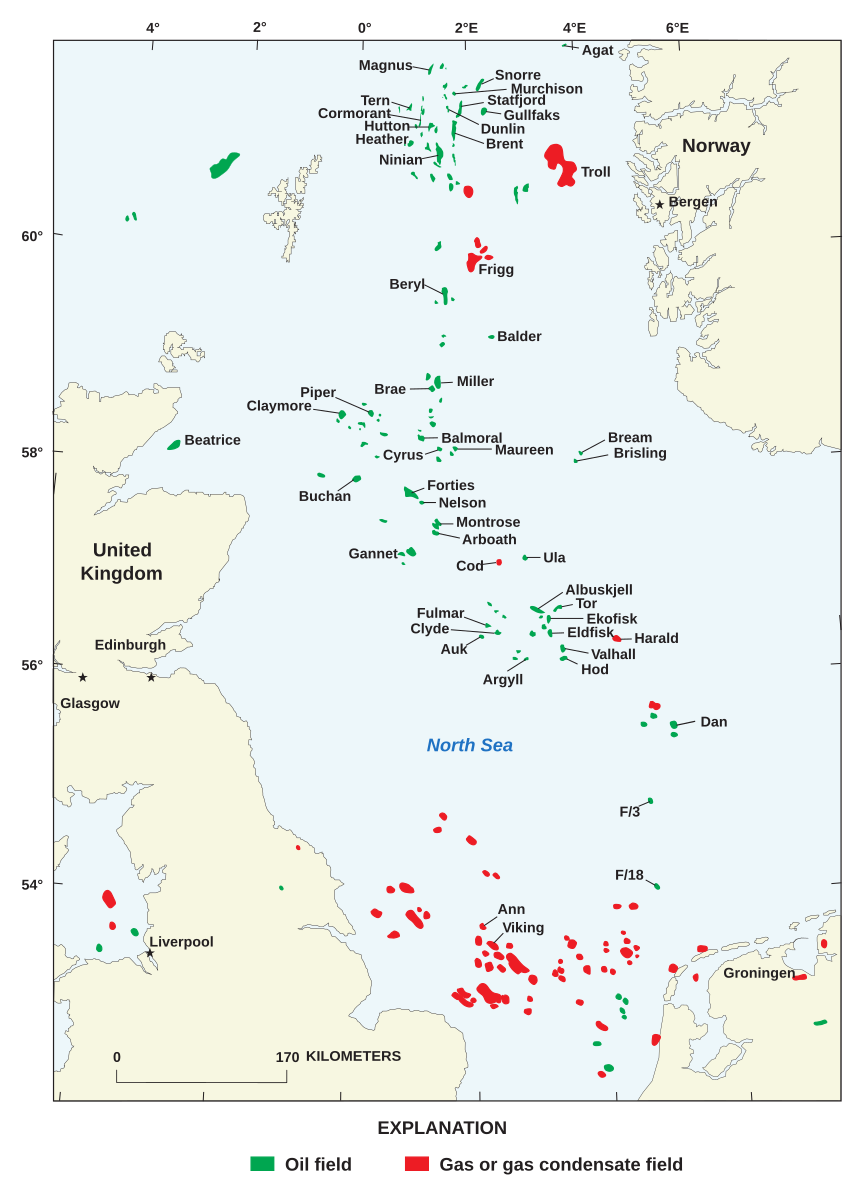

A quick glance at any modern map of the North Sea floor reveals a complex underwater patchwork of names, some familiar (Argyll, Clyde, Tyne), some less so, and many which the uninitiated may hesitate to try to pronounce (Schiehallion, Gjøa, Albuskjell). Largely hidden beneath the waves, these are places where state-of-the-art technology and hard-edged commercial interests improbably converge with national pride, rosy nostalgia and some serious romanticism.

It is, after all, the oil and gas companies themselves who have the privilege of christening their fields as they come online, subject to approval by the relevant national body — the North Sea Transition Authority in the UK, the Norwegian Offshore Directorate in Norway. Of the various participating countries, each has its own unwritten naming conventions.

Starting in the far south, the naturally pragmatic Dutch have tended to leave their fields unnamed, instead relying on straightforward labels which reference an efficient if rather mundane grid-based system of quadrants and blocks (L8, L10, K13). That said, the Netherland’s proud maritime history is not totally absent. We do encounter the famous admiral and all-round Dutch hero Michiel de Ruyter, in blocks P10 and P11b, as well as the Logger and Kotter fields (L16, K188), which honour two traditional types of fishing boat from an earlier age when it was North Sea herring that powered the Dutch economy.

Head north from here and you meet the various British and Norwegian fields — and an eclectic mix of names along the way, though by no means a random, scattergun collection. Recurring themes run through the map like undersea pipelines, linking dispersed fields to form onomastic sets.

The natural world is here in abundance: local sea birds are prominent in the fields named by Shell (Auk, Cormorant, Fulmar, Guillemot, Kittiwake, Skua, Tern), and there are nods to various Scottish lochs and mountains (Lomond, Leven, Broom; Foinaven, Schiehallion). This distinctly Scottish flavour is no surprise given the prominence of Aberdeen in the British oil and gas industry, and is about as subtle as an Edinburgh tourist gift-shop, with fields named Alba, Caledonia, Saltire, Tartan and Thistle.

But the naming of these reserves beneath the waves extends beyond the literal. A large number of the Norwegian fields honour figures from Norse mythology: Njord, god of the sea and all its riches, is of course represented, as are Tor and Odin, extending even to Odin’s spear (Gugne) and his eight-legged horse (Sleipner). From the west, across the other side of the North Sea, Machar, Magnus, Mungo and Columba are memorialised as early medieval saints of the British Isles, albeit in this rather surprisingly modern context. The mysterious Picts even earn their (rightful) place on the lucrative sea-bed.

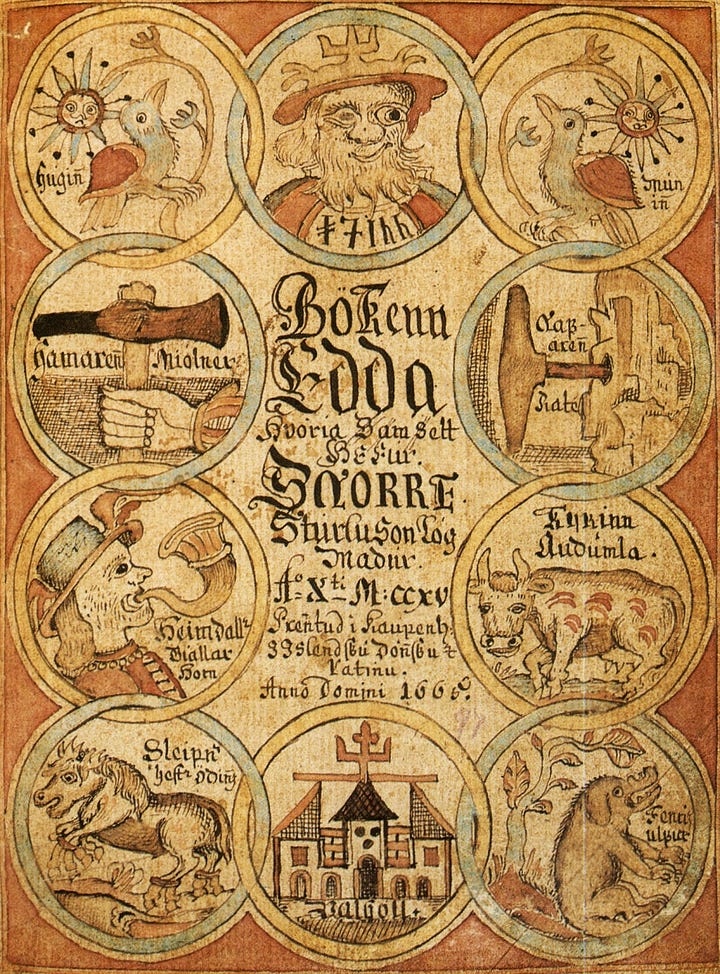

Back on the Norwegian side, the Vikings, that cornerstone of Norse heritage and identity, have left their mark in other ways, beyond their pagan gods. King Olaf Tryggvason’s mighty tenth-century longship lends its name to the Ormen Lange field, and the famous Oseberg and Tune Viking ship burials are similarly acknowledged. Even Snorri Sturluson, the famed medieval Icelandic poet, has his own Norwegian field, as incidentally does Walter Scott in the UK sector, naturally alongside his famous novels Ivanhoe and Rob Roy. I wonder what Snorri and Scott would think about their literacy legacy being honoured by an industry neither could have dreamed of, despite their vivid imaginations.

As Sheila Young of the University of Aberdeen pointed out in her 2009 prize-winning essay on oil and gas field names in the North Sea, these names only serve their purpose while the relevant field is being developed, is actually producing or is being decommissioned: post-decommission, a field name, like its abandoned undersea referent, has little use.

As the North Sea oil and gas industry faces a future of managed decline, what will become of its peculiar and culturally revealing nomenclature? While they may soon fade into obscurity, these names will always remain a valuable window onto the cultural identities and imaginations of those who drove and benefited from the industry’s golden age.

Maureen, Beatrice and Beryl. I wonder what these women think about the areas named after them?