This post is the first in a new monthly series bringing together some North Sea news stories which caught my eye this month. This is a newsletter platform, after all.

August’s dispatches span the freshly discovered, the newly recovered and the thoughtfully restored. All are testament to just how much the North Sea still has to give.

Normal service resumes next week.

Rogue waves: explaining the extreme

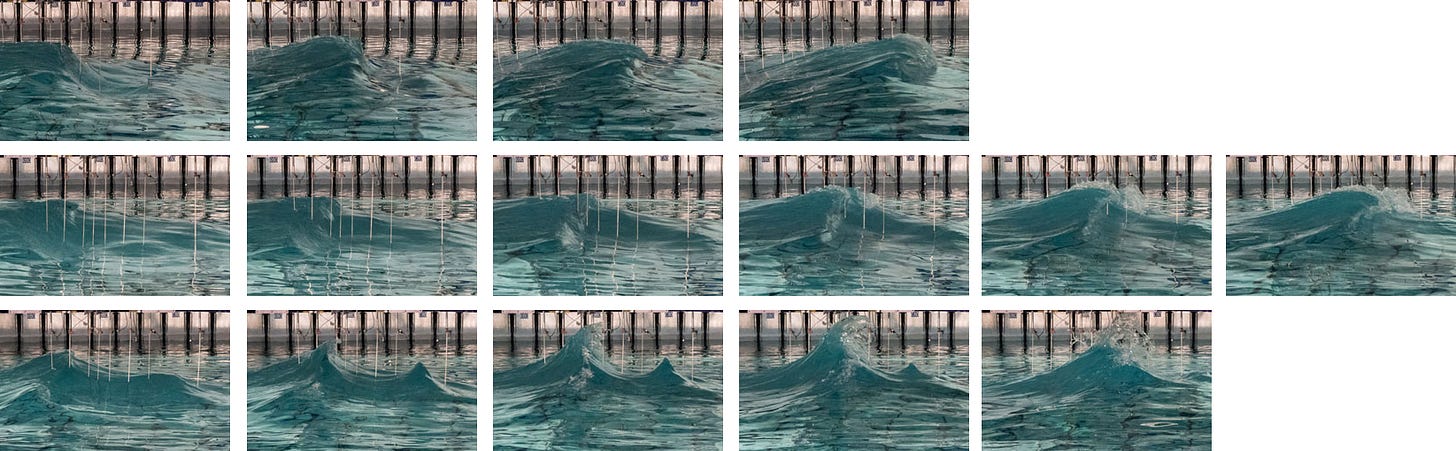

Giant, one-off waves which appear out of nowhere and retreat just as fast have long been feared by seafarers. These rogue waves, as they are known, have also been the target of scientific inquiry, especially since News Year’s Day 1995, when the first actual recording of a rogue wave came in from the middle of the North Sea, picked up fortuitously by a measuring device on the Draupner offshore platform. The official recording of the twenty-five metre high Draupner Wave at last confirmed what mariners had been whispering for years — and the race began to find a satisfactory explanation for these extreme and potentially devastating events.

Now, a new study of North Sea data has brought us one step closer to understanding how rogue waves form in open water. A research team led by Francesco Fedele, a specialist in wave mechanics at Georgia Institute of Technology, examined 18 years’ worth of measurements from an offshore platform in the Ekofisk field. As Fedele put it in his recent piece for The Conversation, the ingredients for these giant waves are, in fact, normal-sized:

Rogue waves form when lots of smaller waves line up and their steeper crests begin to stack, building up into a single, massive wave that briefly rises far above its surroundings. All it takes for a peaceful boat ride to turn into a bad day at sea is a moment when many ordinary waves converge and stack.1

Apart from satisfying sheer intellectual curiosity, why does this matter? Freak phenomena are by definition inexplicable, and thus unpredictable. A better understanding of rogue waves — downgrading them from freak to accountable — means we can forecast and pre-empt them, which is surely in the interest of all those who ever venture out onto the open sea.

When events turn: scuttled British cannons found off Heligoland

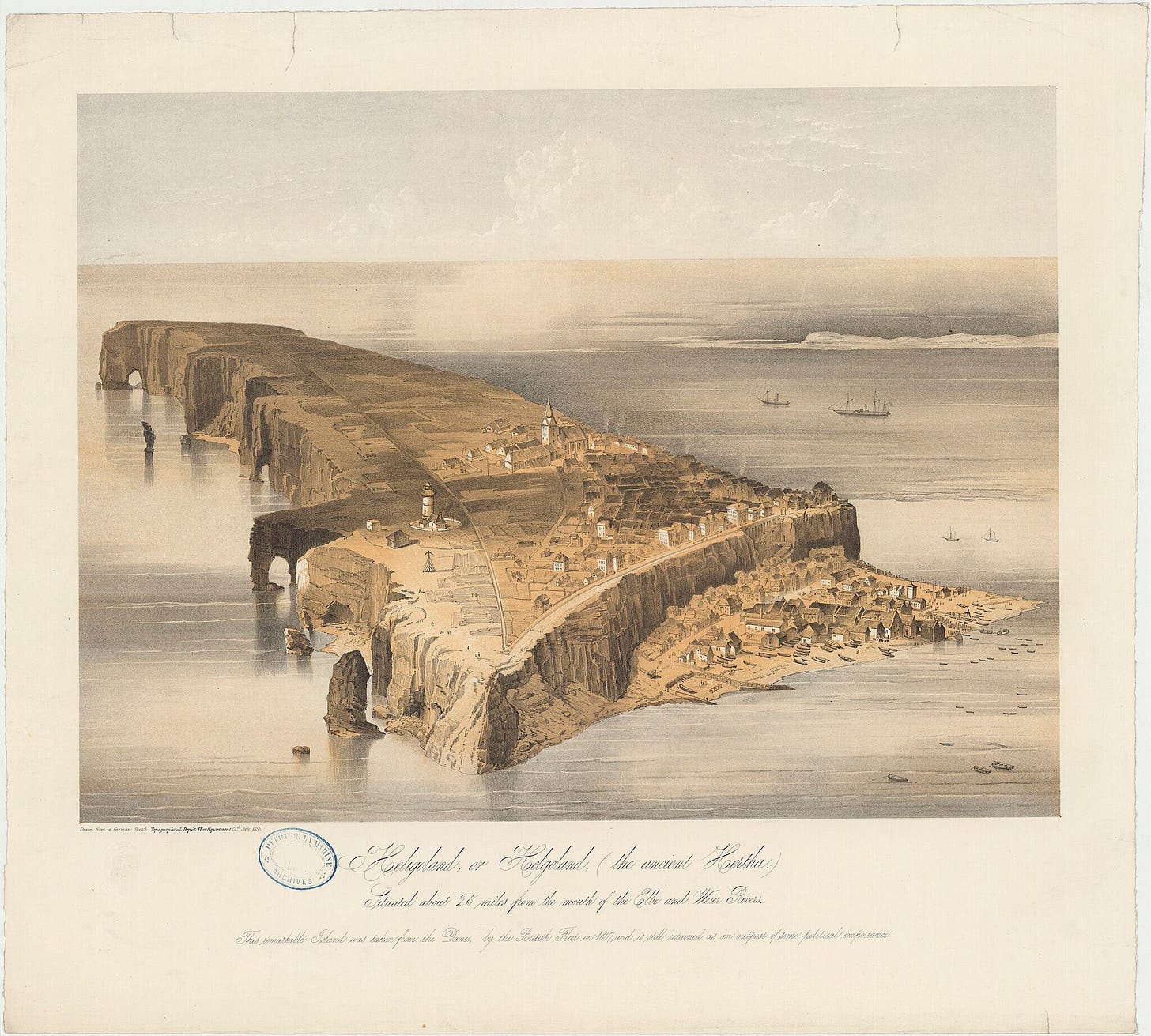

Meanwhile, out to the east, in the much fabled German Bight, subsea divers continue to come across intriguing spots of underwater heritage. Sixteen submerged cannons have turned up in a recent survey of the waters around Heligoland. The weapons are unmistakably British, bearing distinctive Blomefield rings, as well as broad arrow ordnance markings and the monogram of King George III. Curiously, there is no sign of a nearby shipwreck, indicating that the weapons likely found their way to the sea floor not through misfortune, but in a deliberate act of self-destruction.

The rediscovered cannons date from a time when Heligoland was indeed a British outpost. Ceded to Britain from Denmark in 1814, before too long Heligoland became a popular spa resort for Europe’s upper classes. Heinrich Heine was among the many visitors who sought out the far-flung archipelago and its famed fresh air. But with German unification came increased scrutiny of nationalist interests, and Heligoland just so happened to command the North Sea entrance to the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal (later Kiel Canal), an ambitious project to carve out a critical link through to the Baltic and an in-house connection between the twin seas on Germany’s doorstep.

No more than a tiny red sandstone speck tucked neatly away in one corner of the North Sea, Heligoland was coming into focus as an unlikely host for one of Europe’s great modern rivalries, a status it would hold on to well into the twentieth century, as I have written about before. In 1890, Britain ceded Heligoland to Germany. In return, Germany would recognise British authority in Zanzibar, and hand over other key East African interests. Events were turning in the world and the British guns on Heligoland, now obsolete, were likely scuttled just before the handover. After all, the best military equipment is only advantageous if it remains in the right hands.

Scuttled remains like the Heligoland cannons remind us that, in the turn of grand events, what would have previously seemed rash or unthinkable can quickly become strategically necessary.

No ordinary transport link: remembering the Shetland Bus

And finally to Shetland, to the village of Scalloway, where a historic slipway has been thoughtfully restored. Originally built in the 1940s, when Shetlander’s links to their Norwegian neighbours would need to be stronger than ever, the Scalloway slipway played a key role in what came to be known as the Shetland Bus — the clandestine operation to ferry special agents, weapons and other supplies across the North Sea and into Nazi-occupied Norway during the Second World War.

With crossings made mostly in winter and sensibly under the cover of darkness, the vessels of the Shetland Bus were often in need of serious repair on their return to Shetland — and so the Scalloway slipway was built. It was and still is named after the then Crown Prince Olav of Norway, who sought refuge during the war in Britain with the rest of the Norwegian royal family, and personally visited the slipway once it was built.

There were reportedly plenty of Norwegians at the official opening of the newly restored slipway earlier this month. Fittingly, among the guests was Tom Georg Indrevik, mayor of Øygarden on Norway’s west coast — the home port of the first Shetland Bus vessel to make use of the original wartime slipway.

The best of the rest

New research reveals the reasons behind the West’s reluctance to eat seaweed

Scapa Flow in Orkney gets Historic Marine Protected Area status

A new book on the history of human resilience in farming the North Sea coast

I knew that Heligoland had changed hands. Thank you for more background on that event.

"one-off waves which appear out of nowhere". This suggests that a rogue wave might arise in calm sea. The Draupner wave was twice the height of the other waves as are other recognised rogue waves.