Compared to their continental neighbours, the English were not much good at glass-making, nor glass-painting for that matter.

Having retreated with the Romans, glazing was yet another skill to be revived and re-nurtured in early-medieval England with whatever know-how could be procured, near or far. Bede tells us that, when wishing to glaze the windows of his new church at Wearmouth in the seventh century, Abbot Benedict Biscop ‘sent messengers to Gaul to fetch makers of glass (…) who were at this time unknown in Britain’.1

Benedict’s imported expertise doesn’t appear to have endured in Northumbria. In 764, nearly a century after the Gallic glaziers were summoned to Wearmouth, Benedict’s successor, Abbot Cuthbert, was again in need of expertise from across the sea. In a letter to Bishop Lul of Mainz, a fellow Anglo-Saxon, Cuthbert asks:

if there is any man in your diocese who can make vessels of glass well, that you will deign to send him to me when time is favourable. But if perhaps he is beyond your boundaries outside your diocese in the power of some other, I ask your brotherly kindness to urge him to come here to us, because we are ignorant and destitute of that art.2

Earlier in the letter, Abbot Cuthbert offers us a clue as to the need for glass windows on the harsh Northumbrian coast, when he informs Lul that ‘the conditions of the past winter oppressed the island of our race very horribly with cold and ice and long and widespread storms of wind and rain’.

If the cruel island climate was a practical reason to be in want of glass, the accompanying grey skies gave glaziers reason to transcend the functional. As June Osborne notes in the opening chapter of her book on the history of stained glass in England, coloured glass is better suited to infinitely variable northern skies than unwavering, bright sunshine. Soft diffused sunlight on a cloudy day in fact enhances stained glass: ‘hues intensify or merge, faces and figures come into prominence or fade and scenes are created or lost’.3

Just as England’s skies offered the ideal thin light for showcasing stained glass in all its artistic subtleties, so too did those of neighbouring Flanders, where storms and squalls of a shared weather system rolled in from across the Southern North Sea. Indeed, it was Flemish glaziers who would come to catch the eye of the highest English elites across the short stretch of water.

In 1449, Henry VI entrusted John of Utynam, a Flemish glazier, to make coloured glass destined for windows at that most English of institutions, Eton College. In a legal first, the Crown granted the Fleming exclusive rights to arrange, prepare and produce stained glass in England for twenty years — England’s first recorded patent of invention.4

Many glaziers from the Low Countries later followed in John of Utynam’s footsteps, similarly enticed by offers from the top too good to refuse. Barnard Flower and Galyon Hone are two notable examples, both Antwerp-trained and together responsible for the ambitious windows of King’s College Chapel, Cambridge. Flower had been in the employ of Henry VII since 1496, who described him as ‘well expert and cunning [knowledgeable] in the art of glazing’, and in 1505 he was duly appointed King’s Glazier, the very pinnacle of his trade.5

Tasked with the mammoth project at King’s in February 1516, it took Flower and his men eighteen months to produce the first four windows alone and so, when Flower died in the summer of 1517, the work still had a long way to go. Flower’s successor as King’s Glazier and on the commission at King’s was one of his assistants, Bruges-born Galyon Hone. Like Flower, Hone presumably felt reasonably at home among the low-lying Cambridgeshire Fens, and at any rate had the favour of Henry VIII to soften any animosity from his increasingly disgruntled English competitors in the glazing trade.

Hone’s artistic work is still coveted today, it appears; in 2016, a stained-glass window attributed to him was apparently stolen to order from the Tudor-age Withcote Chapel in Leicestershire. As was noted at the time: “It's not something you might just stroll across and decide you want to steal - a stained glass panel”.

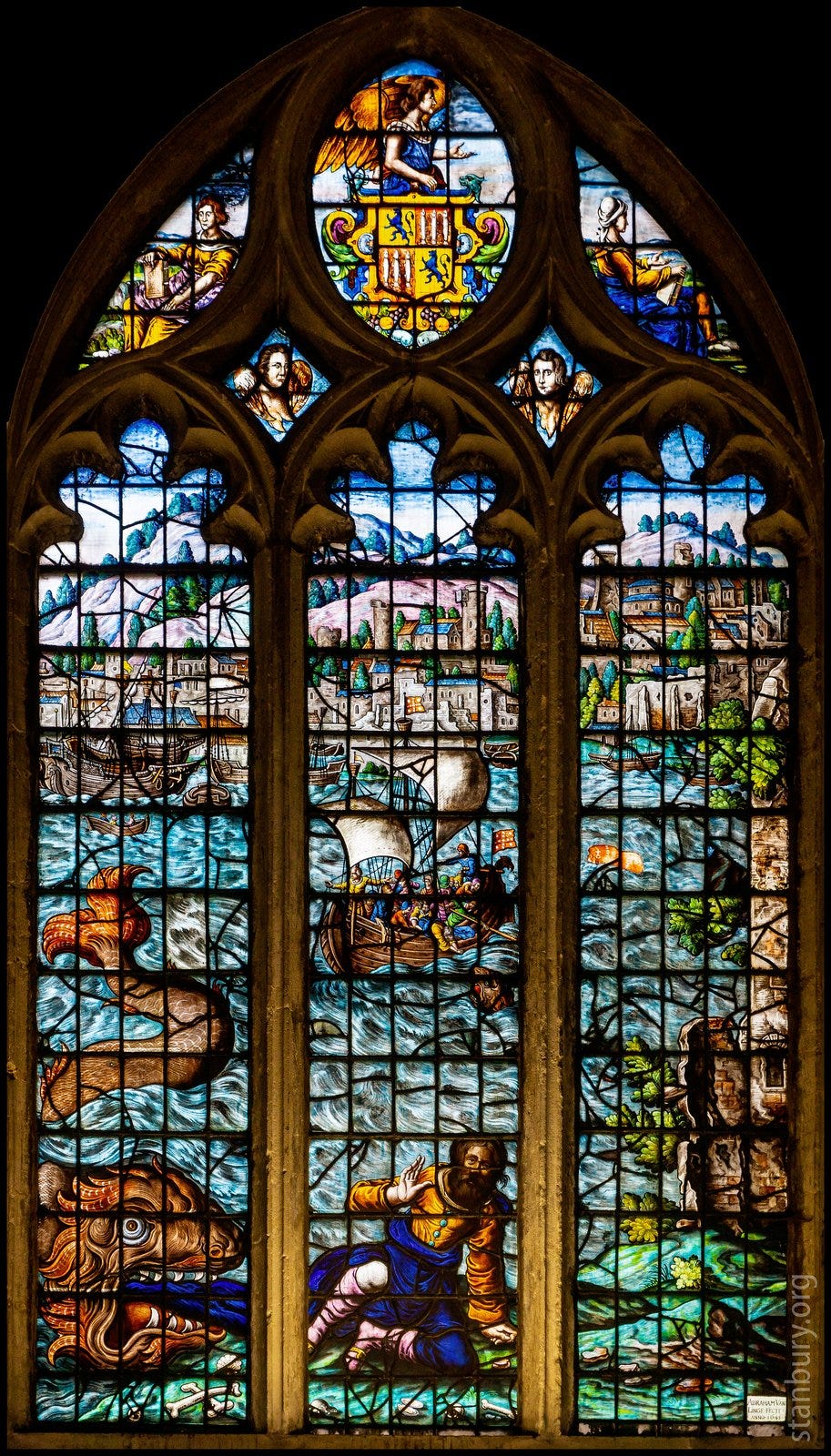

By the seventeenth century, foreign glaziers were still very much active in England, though rivalries with native glass-workers were fierce as ever. Newly arrived Bernard van Linge, who hailed from a renowned family of glass-painters from Emden, East Frisia, was finding it hard to obtain work in London as a result of the tensions. Fortuitously, he was introduced to the warden of Wadham College, Oxford, that other great English educational institution where, in 1621, he was commissioned to create the east window in the college chapel.6

Before returning to the Continent in 1623, Bernard would leave his mark on the windows of several Oxford college chapels, among them those of Balliol and Lincoln College, as would his younger brother, Abraham van Linge, who remained in England long after his brother’s departure.

John of Utynam, Barnard Flower, Galyon Hone, Bernard and Abraham van Linge — these are just a few of the names we remember of the many glass-painters who crossed the North Sea to make their mark on some of England’s most famous institutions. But behind these precious few stand hundreds if not thousands of unsung others. Though anonymous, their influence endures in the windows they worked, and in other ways too.

Language change requires numbers and communities, not just a few celebrated individuals, and the largely nameless Netherlandish glaziers are reflected in the language they left behind. The traditional stained glass technique of grozing — the careful crumbling away of bits of glass to fashion the exactly required shape for a design — is reckoned to derive from Dutch gruizen, meaning ‘to crush’ or ‘to grind’; a small but lasting trace of a centuries-long artistic exchange.

Bede, The lives of the holy abbots at Weremouth and Jarrow. In J. A. Giles (Trans.), The historical works of Venerable Bede (London: Bohn, 1843), p. 87.

Dorothy Whitelock (ed.), English historical documents, c. 500-1042 (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1955), 185 p. 766.

June Osborne, Stained glass in England (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1993), p. 4.

Marcio Luis Ferreira Nascimento & Edgar Dutra Zanotto, On the first patents, key inventions and research manuscripts about glass science & technology. World Patent Information 47, 2016, pp. 54-66.

Carola Hicks, The King's glass: A story of Tudor power and secret art. (London: Chatto & Windus, 2007) pp. 81-82.

Osborne may be right about the type of light that’s best for appreciating the glass itself, but I gotta say that I love seeing the myriad refracted colors hitting grey stone when the sun is shining. Otherworldly.

A wonderful piece of (art) history I knew little to none about. Well written too!