'A show of the world in every sense of the word'

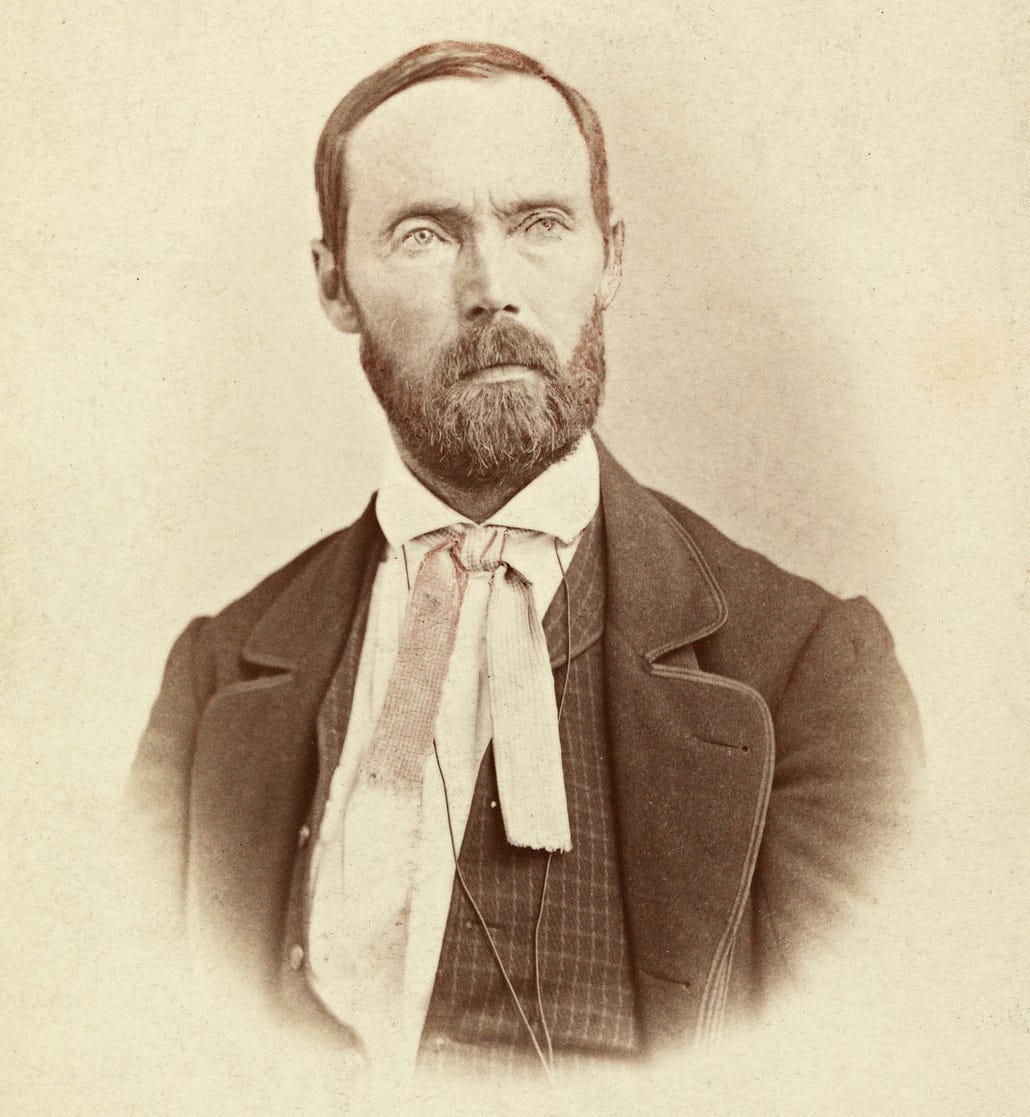

Aasmund Olavsson Vinje's visit to Victorian Britain

The planning had been plagued by setbacks, but at last London’s International Exhibition of 1862 was officially open, if a year late on account of the Second Italian War of Independence and resulting turmoil on the Continent.

Closer to home, the recent death of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s much-loved consort and the driving force behind the success of the 1851 Great Exhibition, provided a sombre backdrop to proceedings. The Queen herself remained in private mourning and was poignantly replaced by an empty throne at the official opening ceremony on the 1st of May.

Over the coming months, some six million visitors would flock to this latest World Fair, wandering the vast halls of the purpose-built Exhibition Palace in South Kensington, marvelling at thousands of wonders in engineering, manufacturing, art and design from over thirty-nine countries.1 With many foreign dignitaries in attendance, fierce national rivalries could be played out through relatively innocuous displays of steel and steam, gold and glass, cotton and ceramics.

Among the foreign visitors was a Norwegian journalist by the name of Aasmund Olavsson Vinje, editor and founder of Dølen (‘The Dalesman’), a modest weekly magazine covering art, travel, politics and language in his native homeland.

Profoundly interested in modernisation and its societal consequences, Vinje found much to chew on amongst the 28,000 or so exhibits, later recounting how he spent weeks at the exhibition which was, in his view, ‘a show of the world in every sense of the word’.2 A contemporary guide to the exhibition remarks that Vinje’s own Norway presented ‘a small but interesting collection’, ranging from anchors and sledges, to wood carvings and landscape paintings.3

As for the supposedly benign rivalries on display, Vinje was himself rather sceptical:

And yet people dream that such exhibitions are the real promoters of peace! They are rivalry, and must as such promote war. Envy and mercantile opposition displayed on so great a scale are not likely to promote peace, whatever else they do. They will drive individuals and nations to loggerheads. They have done so since the creation of mankind.4

Besides, Vinje’s trip to Britain hadn’t been motivated by any particular desire to visit the Great Exhibition in the first place. Rather, in his application for a government travel grant to support his journey, his stated intention was to travel ‘to northern England, and especially to Scotland, to investigate the local civic infrastructure and legislative situation with consistent reference to traditions and everyday life’.5

Sure enough, Vinje soon ‘got tired of London, its bustle and its din’, travelling north to Glencoe, which he found much more familiar than South Kensington:

It is indeed set down as the most romantic dale in the Scottish Highlands. It much resembles, on a small scale, the Vestfiordale, and many of our Norse dales. The very same features and formations of valleys and mountains present themselves to you, and were it not its treeless aspect, you might, standing there, dream that you were at home.6

Vinje had himself grown up on a small farm in rural Telemark, working as a shepherd boy during his childhood. Like many Norwegian artists and intellectuals of his time, he had an intense reverence for the landscapes, traditions and ways-of-life to be found in the deep valleys and fjords of his homeland.

For many of Vinje’s peers, this wave of National Romanticism manifested itself in nostalgic paintings (see Hans Gude) and folk-inspired compositions (think Edvard Grieg), but Vinje’s own chosen vehicle of national expression was language. With his magazine Dølen, he was one of the first to publish regularly in Ivar Aasen’s fledging Landsmaal (‘Country Language’), a new written standard based on rural dialects, and a pointed response to the Danish-influenced language of upper/middle-class city-dwellers. The seeds were being sown for today’s rather complex language situation in Norway, where both Bokmål (‘Book Language’) and Nynorsk (‘New Norwegian’) coexist as official written standards.7

Once in Scotland, Vinje stayed for some ninth months, basing himself in Edinburgh for the most part. The lasting legacy of his visit was A Norseman's Views of Britain and the British, a travelogue of his journey, published in Edinburgh in 1863, around a fortnight before he returned to Norway.8

The result is a fascinating and at times witty take on Victorian Britain, replete with admiration, as well as fair social criticism. There are lighter observations, for example, regarding British preferences for naming animals:

Caesar is a very common name for dogs, but Napoleon has not as yet got further than horses. When more hallowed by time, he will certainly rank with dogs.9

… as well as apparent surprises which challenge Vinje’s view of the Victorian temperament:

I came to Britain with the common prejudice of the Continent, that the British were a grave and reserved people […] To me they seem to be at once as open and confiding as I could wish […] compared with us and the Germans, they are lively and pleasing. They must not, however, be judged from their appearances on the streets, where they move along as if they were trees, all of a sudden endowed with a talent for walking.10

But, unsurprisingly, it is modernity in all its effects which appears to have left the starkest impression on Vinje:

The British docks, wharves, dock-yards, tunnels, bridges, archways, and canals, are things to be seen and remembered. […] I felt hurt, nevertheless, at seeing such contrasts of wealth and poverty in this lovely land. A dark ground with the bushes and the grass stunted by the overshadowing of great trees — such is the appearance of Britain with its nobles and ignobles.11

After all, a true friend doesn’t tell you only what you desire to hear.

Aasmund Olavsson Vinje, A Norseman's Views of Britain and the British (Edinburgh: William P. Nimmo, 1863) p. 1, 6.

John Hollingshead, A concise history of the International Exhibition of 1862 : its rise and progress, its building and features and a summary of all former exhibitions (London: Printed for Her Majesty's Commissioners, 1862), p. 118, 122.

Vinje, A Norseman’s Views, p. 7.

Guy Puzey, Ein målmann dristar seg ut: Aasmund Olavsson Vinje in Edinburgh and the Emerging Nynorsk World View. In Christian Cooijmans (ed.), Islands of Place and Space: A Festschrift in Honour of Arne Kruse. (Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies, 2023), pp. 70-109.

Vinje, A Norseman’s Views, p. 11.

Today, Vinje’s important contribution to Nynorsk is remembered with the annual Storegut Prize, named after his poetry collection of 1866, which is awarded for positive use of Nynorsk in the public sphere.

Puzey, Ein målmann dristar seg ut, p. 83.

Vinje, A Norseman’s Views, p. 6.

Vinje, A Norseman’s Views, pp. 20-1.

Vinje, A Norseman’s Views, pp. 147-9.

Thanks for this article and also for introducing me to the painter Christian Skredsvig. I found the comments he made about Victorian Britain very interesting.

So interesting! I can't figure out what he means by the tree comment.. that we walk slowly? Or are knobbly?