A view from the dunes, hoverfly stopovers and hidden traces of a cosmic encounter

North Sea Dispatches #02

This post is the second in a monthly series bringing together some North Sea news stories which caught my eye this month. This is a newsletter platform, after all.

September’s dispatches span the panoramic, the far-flung and even the extra-terrestrial. All are testament to just how much the North Sea still has to give.

Future of unique North Sea seascape secured

The coastal villages and landscapes surrounding the North Sea have inspired countless seascapes over the centuries but, among them all, the Mesdag Panorama is pretty unique. The 14-metre-high cylindrical painting rewards those who enter it with a 360-degree view of the North Sea coast, The Hague and the nearby fishing village and seaside resort of Scheveningen — as they were some 150 years ago.

On entering, the viewer is not only transported to the top of the Seinpostduin, a once famous highpoint among the local sand dunes, but also back in time. From white-bonneted fishwives to ladies of leisure with sun parasols, horse-drawn bathing carriages, traditional sailboats and the odd steamer on the horizon, the full sweep of life on the late nineteenth-century Dutch coast is captured in meticulous detail.

The painting is the work of Groningen-born artist Hendrik Willem Mesdag (1831-1915) who, together with his wife Sientje, chose to make a house on the Laan van Meerdervoort avenue in The Hague his home in 1869, a move which would in time inspire a great many seascapes. Mesdag was seemingly content to dedicate himself to the North Sea on his doorstep, in all its subdued moods, having reflected:

Holland is a grey country, often gloomy. The sentiment of Holland’s atmosphere is melancholy. The sea has usually its saffron note. The only nature I know and am competent to paint is the nature of Holland, and should I undertake to paint clear or softly glowing skies, and limpid, deep-toned, sparkling water, imagination alone would have to be my mentor.1

But the 1881 panorama — which Mesdag completed in four months with the assistance of his wife, as well as fellow Dutch painters Théophile de Bock and George Hendrik Breitner — is by far his most famous. A certain contemporary by the name of Vincent Van Gogh is reported to have been particularly impressed on seeing the work, having declared ‘the only shortcoming of the painting is that it has no shortcomings’.2

Panorama paintings were a popular artistic genre in the nineteenth century, offering the magical possibility of visual transportation in a time before cinema, though many have been lost over the years. The Mesdag Panorama is thus an important survivor of this forgone genre, and has been housed in a dedicated building in The Hague since its creation, making it the oldest surviving panorama painting still on display in its original location.

That said, despite the special status of the artwork at its heart, the Mesdag Museum had reportedly been suffering from financial troubles in recent years. But, earlier this month, the Dutch government announced that it will at last become a national museum from 2026, bringing a funding boost of 1.8 million euros per year.

The Netherlands’ largest painting should now be secured for many future generations to enjoy.

North Sea oil rig revealed to play a role in long-distance pollination

Meanwhile, out at sea, the North Sea’s far-flung oil rigs have taken on a new dimension, thanks to an unlikely collaboration between an offshore worker and ecologists on dry land.

Reportedly, it all started when offshore engineer Craig Hannah — also a keen naturalist, as it happens — noticed a curious phenomenon while working on a platform in the Britannia oil field, some 200 kilometres off the Scottish coast. Clouds of insects would arrive on the rig, sit for a few hours on its upper reaches, before flying off, once more out into the open sea. So struck was Hannah that he contacted the University of Exeter’s Centre for Ecology and Conservation. Several conversations and shipped samples later, a research collaboration was born that has now shed some light on what the insects could be up to.

The insects turned out to be hoverflies in the main — the planet’s most important pollinators, after bees. Analysis of pollen on the sampled hoverflies revealed that it came from as far as 500 kilometres away, and from a dazzling array of over 100 different plant species. (The fact that oil rigs do not generally feature local flowering plants meant that the research team could safely identify the pollen as having arrived with the flies themselves — a benefit from the far-flung offshore environment).3

Hoverflies are known to be highly mobile, migrating over long distances with the seasons, and the researchers concluded from their sudden arrival and departure that the insects use the oil rigs as a handy stopover point. What Craig Hannah had seen was merely some fellow creatures enjoying a well-deserved break on an impressively long journey.

Hidden traces of a cosmic encounter beneath the sea floor

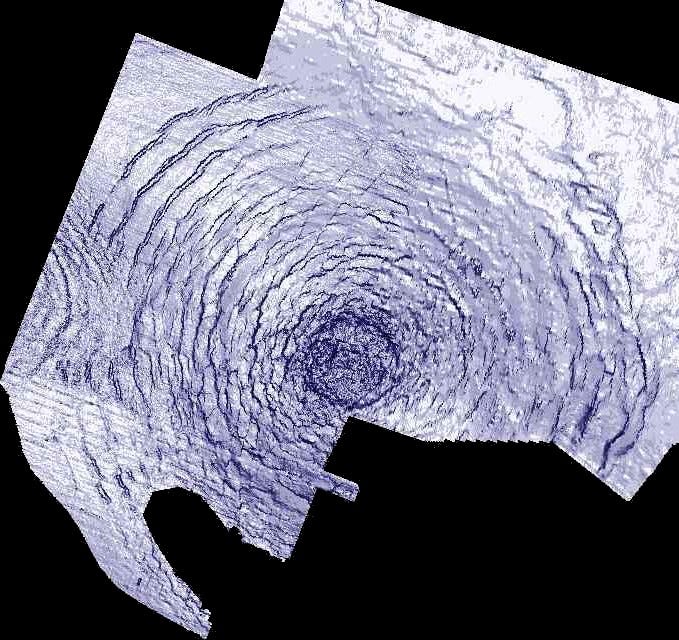

And finally to the depths of the sea, and indeed beyond, to the Silverpit crater, a distinct set of concentric rings 700 metres beneath the seabed, off the East Yorkshire coast. Ever since the buried crater was discovered by petroleum geoscientists Philip Allen and Simon Steward in 2002, the question of how it came to be has been a matter of scientific debate.

Now, a new study indicates that the crater was born of an asteroid collision over 43 million years ago, a cosmic encounter on the then seabed. Especially crucial was the analysis of some recovered rare quartz samples, whose particular make-up can only have come about under extreme shock pressures.

Within minutes of the impact of the asteroid, itself reckoned to be a staggering 160 metres wide, a 1.5-kilometre high curtain of rock and water arose, before collapsing into the sea and prompting a tsunami, as the simulation below captures.

A terrifying prospect, even with the vast distance of several million years.

The best of the rest

King’s Lynn keeping the North Sea’s brown shrimp tradition alive

Shapeshifting waterhorse from Norse folklore recognised with new sculpture in Shetland

Frederick W. Morton, The art of Hendrik Willem Mesdag. Brush and Pencil 11(5), 1903, pp. 324-5.

Luke McKernan, Panoramic space and the Mesdag show. In Ian Christie (ed.), Spaces: Exploring spatial experiences of representation and reception in screen media (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2024), p. 26.

Toby D. Doyle, Eva Jimenez-Guri, Jaimie C. Barnes, Craig Hannah, Simon Murray, Christopher D. R. Wyatt, Oliver M. Poole & Karl R. Wotton. Long-range pollen transport across the North Sea: Insights from migratory hoverflies landing on a remote oil rig. Journal of Animal Ecology 00, 2025, pp. 1–15.

Thanks Hannah. I find your newsletters incredibly informative. And they deepen the bond I feel between the East coast of England, a place I am discovering anew and the Low Countries when I have lived and worked off and on throughout my career.