Guy Fawkes, faith and Flanders

Plus the inevitable fireworks (though not where you'd necessarily expect them)

One of the strange things about being a Brit abroad is the coming and going of the 5th of November each year without much ceremony.1 While friends and family in the UK huddle around bonfires in defiance of the seventeenth-century plotters and soggy autumn weather, my November 5th passes with little fanfare these days. (Though now living in a country where, as we’ll see below, the national disposition is towards pyromania, it’s highly possible that some local bangs and pops will coincide by chance with the evening of the 5th).

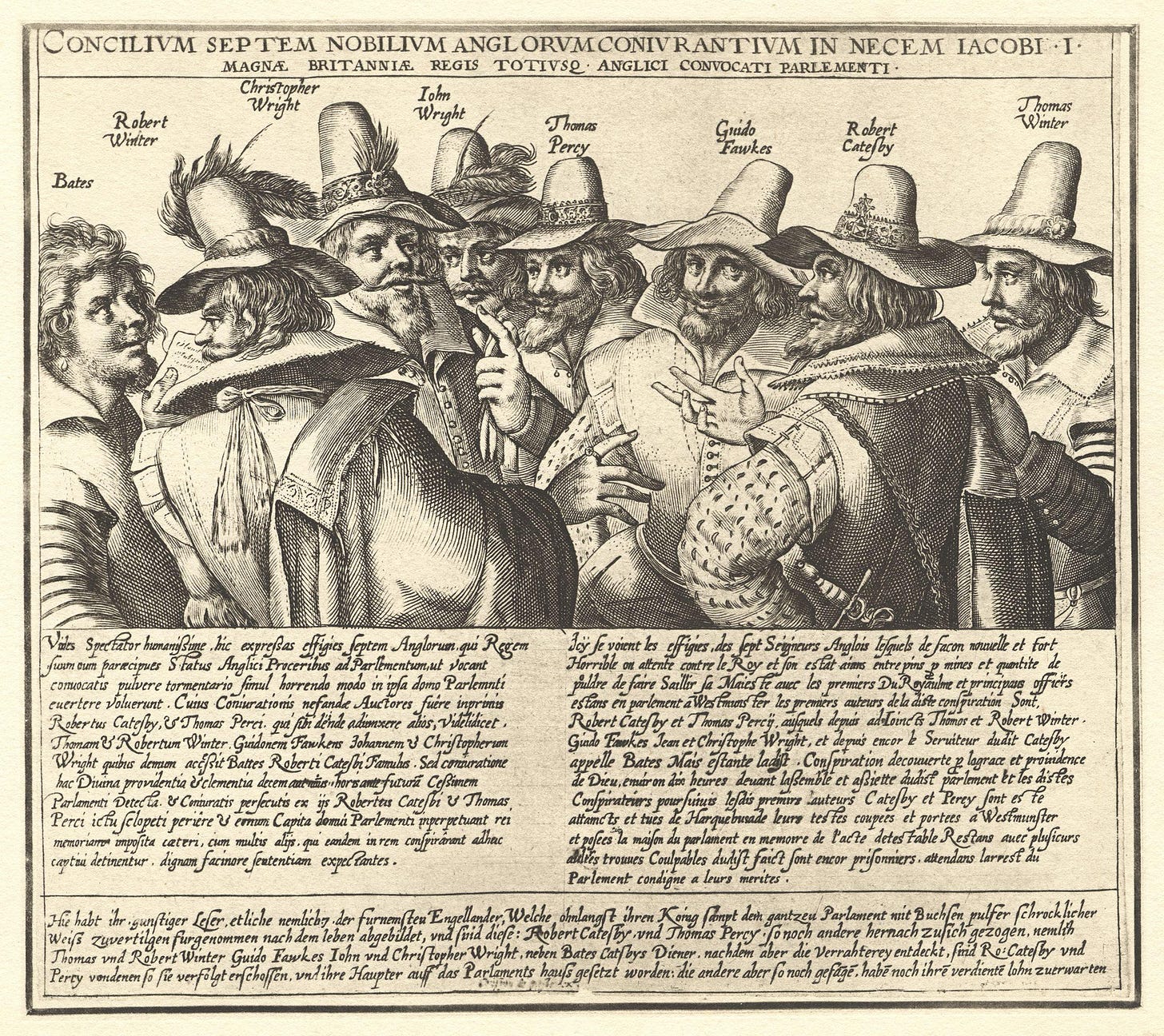

While Bonfire Night remains an unmistakably British tradition, the scheming behind the original Gunpowder Plot stretched to foreign shores, in particular the Low Countries. Three of the plotters depicted in the famous engraving in London’s National Portrait Gallery — incidentally the work of Antwerp-born Crispijn de Passe the Elder — are known to have spent significant time in Flanders.

The Low Countries at the time were split along religious lines: the predominantly Catholic Spanish Netherlands in the south, ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburg dynasty, and the United Netherlands Provinces in the north, a breakaway, majority-Protestant republic resulting from a series of revolts.

This division resulted in ongoing waves of migration and population churn, Protestants fleeing north and Catholics south. The Spanish Netherlands, including Flanders, became a point of refuge for Catholics from all over Europe, not least from Elizabethan England where increasing pressure to conform to Protestantism had left many Catholics seeking an easier life. English Catholic nobles established their own monasteries, convents and schools in the territory, Oxbridge men set up their own educational institutions, and young English men from Catholic families joined the multinational Army of Flanders in the service of the King of Spain.2

It is therefore hardly surprising that some of the gunpowder conspirators had become well-acquainted with Flanders in the years before the doomed plot of 1605. Well before his involvement in the conspiracy and his renting of the infamous cellar under the Houses of Parliament, Thomas Percy had served in Flanders under his cousin, the 9th Earl of Northumberland. Thomas Wintour (de Passe’s Winter), meanwhile, had had his own, rather contrary experiences in the region, having fought first against Catholic Spain on behalf of the Protestant rebels, before abruptly switching sides around 1600.3

Back in England by 1604, Wintour was later recruited by plotter-in-chief Robert Catesby and returned to Flanders in the April of that year, seeking “to bring over some confident gentleman” to join the growing band of conspirators.4 Catesby had apparently suggested a certain Guy (Guido) Fawkes, who had served the Spanish in Flanders as a soldier for over a decade, and was thus conveniently anonymous in England. Wintour’s pitch must have seemed convincing to Fawkes, as later that month the two men landed back in England together.5

On the 20th of May 1604, Catesby, Wintour, Percy and Fawkes held their first meeting in a London pub, joined by Percy’s brother-in-law, John Wright.6 Over the coming months, further co-conspirators would be recruited (including one Ambrose Rookwood, previously educated in Flanders), strategic locations rented and gunpowder illicitly sourced. Fawkes returned briefly to the Flanders he knew so well to garner foreign support for the cause, and intended to travel there once again after the treasonous deed was done, to spread the “good news” among the English Catholic exiles.7

Of course, that news was never to come, and Fawkes would never again leave London, never mind board a ship across the sea. Following an anonymous tip-off, on the night of November the 4th Fawkes was discovered in the cellar with a pocket watch, matches and touchwood, along with thirty-six barrels of gunpowder. He was arrested and, following interrogation and torture at the Tower of London, was executed on the 31st of January 1606 in Westminster’s Old Palace Yard, right in front of the Houses of Parliament he had come so close to destroying.8

The first bonfires and fireworks celebrating Fawkes’ failure were lit on the 5th November 1605 itself, in the immediate wake of the foiled plot.9 Recreational fireworks, by this time, had grown to be a popular way to mark a royal occasion or celebrate some victory or other in Early Modern Europe, and were thus a fitting way to mark the conspirator’s failure.

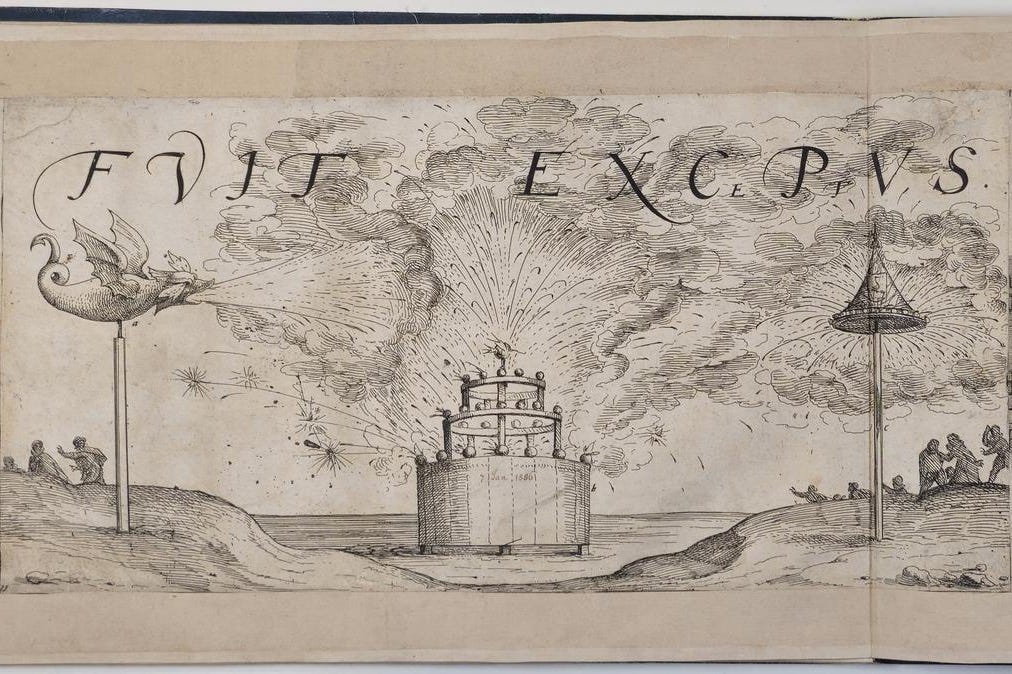

Fireworks were also employed to diplomatic ends, as by the Dutch in December 1585 during their grand reception of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and favourite of Elizabeth I. The Queen had appointed Leicester to command an English expeditionary force to assist the United Provinces in their revolt against Spain, and the Dutch apparently welcomed the support in spectacular fashion. A series of engravings from c. 1586 depicting the arrival of Leicester in The Hague features elaborate seaside firework displays. (The enthusiasm for the incoming Englishman soon faded, however, when he proved to be an incompetent and arrogant commander.)10

The Dutch tradition for over-the-top pyrotechnics is still alive and well today, and can be enjoyed or endured, depending on your persuasion, throughout the darker months and especially at New Year. Here’s just a small taster of last year’s modest New Year’s Eve celebrations in The Hague, some four and a half centuries or so after the Earl of Leicester’s grand arrival.

This year, of course, the 5th of November falls on a Tuesday, and so Bonfire Night coincides with the US Presidential Election, as it has at regular intervals throughout the years — 1996 (won by Clinton), 1968 (Nixon), 1940 (Franklin D. Roosevelt) and 1912 (Wilson).

Peter Guilday, The English Catholic refugees on the continent, 1558-1795 (London: Longmans, Green and Company).

Antonia Fraser, The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and faith in 1605 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1996), pp. 48, 60-61.

A. H. Dodd, The Spanish treason, the Gunpowder Plot, and the Catholic refugees. The English Historical Review 53(212), 1938, pp. 627-650.

Antonia Fraser, The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and faith in 1605 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1996), pp. 87, 119. Guy became known as “Guido” during an (unsuccessful) mission to Spain to seek support for the English Catholics from Philip III and the Spanish Council.

Antonia Fraser, The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and faith in 1605 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1996), pp. 148, 178.

Antonia Fraser, The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and faith in 1605 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1996), p. 352.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester. Encyclopedia Britannica, 31 Aug. 2024.