Looking into the abyss of time

The origins of modern geology on Scotland's North Sea coast

The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time1

This is how Scottish scientist John Playfair would later remember his 1788 excursion to Siccar Point, a rocky headland on Berwickshire’s North Sea coast. A fleeting visit though it was, it would nevertheless come to change how we think about the dizzying scale of time itself.

It was reportedly a fine day for sailing and Playfair, along with fellow Scots James Hutton and James Hall were out scouring the shore for evidence which up to that point had proved only shy and scarce. On landing at Siccar Point, they at last found what Hutton was seeking: a striking and undeniable sight with which to bolster his radically new theory of the Earth.

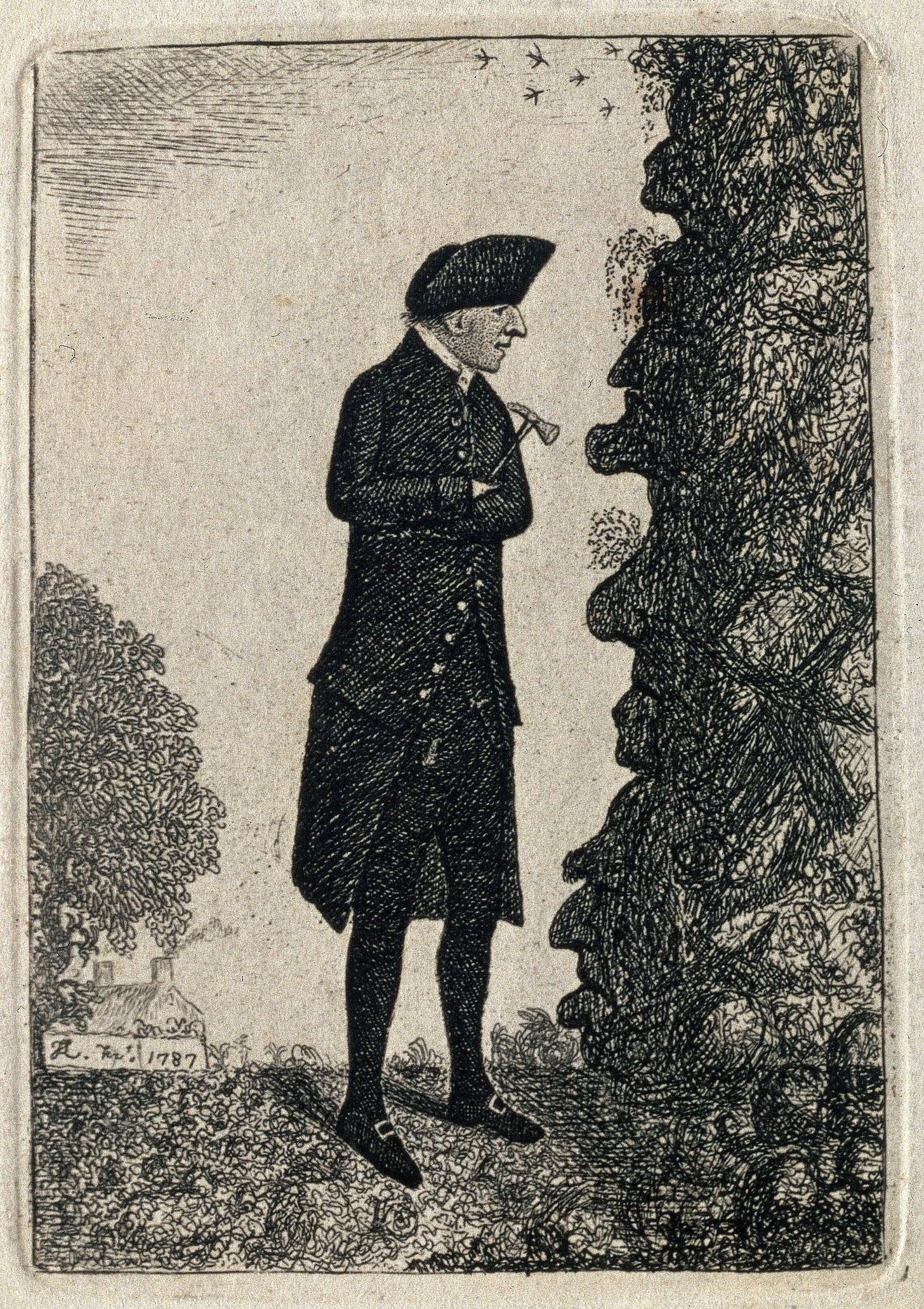

Hutton himself was already into his seventh decade on Earth and, even by the standards of the Scottish Enlightenment, had accrued a staggering range of interests and experiences. A law apprenticeship in Edinburgh, a doctorate in medicine from the University of Leiden, co-founding the Royal Society of Edinburgh, farming in Norfolk and the Scottish Borders, advising on the construction of the Forth & Clyde canal as well as preparations for Captain Cook’s second voyage — James Hutton had seemingly done it all.

But it was the earth beneath his feet that intrigued him most, or had done so at least since his farming days, when he would look ‘with anxious curiosity into every pit, or ditch, or bed of a river that fell in his way’.2 By the late 1780s, Hutton had garnered years of observations and musings regarding the natural history of the globe, and the scars of bygone changes that could still be traced on its surface. Critically, his skills extended beyond mere observation. As Playfair would later recall of his friend after his death:

The eulogy so happily conveyed in the Italian phrase, of osservatore oculatissimo, might most justly be applied to him; for, with an accurate eye for perceiving the characters of natural objects, he had in equal perfection the power of interpreting their signification, and of decyphering those ancient hieroglyphics which record the revolutions of the globe. There may have been other mineralogists, who could describe as well the fracture, the figure, the smell, or the colour of a specimen; but there have been few who equalled him in reading the characters, which tell not only what a fossil is, but what it has been, and declare the series of changes through which it has passed.3

These ‘revolutions of the globe’ spanned the full range of geological processes — erosion, deposition, compression, uplift — and it was the search for discernible traces of these past revolutions which brought Hutton and his companions ashore at Siccar Point on that fine day in 1788.

The sight which met the three men off the boat was a striking example of what is now known as Hutton’s Unconformity — a point where two contrasting types of rock meet each other in a sharp switch from horizontal to vertical bedding patterns. Hutton had already observed and recorded such unconformities on his travels elsewhere in Scotland, on the Isle of Arran and the banks of Jed Water at Jedburgh. But at Siccar Point the angular junction between horizontally-layered red sandstone and upright greywacke beds was, to his delight, even starker.

Here was dramatic visual evidence in support of the theory of the Earth that Hutton had been tentatively advancing — that our planet was unimaginably old, and had been shaped by successive cycles of deposition, uplift and erosion over immense spans of time. Obvious though it may seem today, this was, in the late eighteenth century, a radical departure. After all, was the Earth not a mere six or so millennia old, as the Irish scholar and archbishop James Ussher had apparently definitively calculated in 1650? And had the planet’s surface not been violently shaped by sudden, catastrophic events, most notably Noah’s flood?

As with any break with consensus, Hutton’s need for tangible, persuasive evidence was great. And here was hard evidence one could even walk on. Hutton knew that the vertical greywacke beds must have been significantly older than the red sandstone layers now lying across them, and allowing for a chronological gap long enough for the greywacke beds to have been gradually folded and uplifted into their near-vertical position before the red sandstone was deposited on top. As Playfair recalled:

What clearer evidence could we have had of the different formation of these rocks, and of the long interval which separated their formation, had we actually seen them emerging from the bosom of the deep?4

This glimpse into the ‘abyss of time’ would in turn, through Hutton’s work, radically transform how we think about the natural history of the planet and our fleeting existence on it, liberating the human imagination from all previous senses of beginnings and ends. And, even though the rocks at Siccar Point would themselves continue to morph and transform, this quiet point on the Berwickshire coast would forever be cemented as the place where modern geology and deep time was born.

2026 will mark the 300th anniversary since Hutton’s birth and, looking ahead to this milestone, there is currently an active Crowfunder aiming to raise funds to build a Deep Time Trail at Siccar Point.

John Playfair, Biographical account of the late Dr James Hutton, FRS, Edinburgh. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 5(3)3, 1805, p. 73.

Playfair, Biographical account, p. 44.

Playfair, Biographical account, p. 89.

Playfair, Biographical account, p. 72.

Cool. I had read a bit about Hutton -- what a fascinating thing to be an 18th C person hypothesizing that the Earth was insanely old -- but I had never thought too much about where exactly he was looking for evidence. Siccar Point is interestng; next time I go to Edinborough I might take a day trip out there.