“We’re in a golden age of board games”, proclaimed an article in the Washington Post on Christmas Eve, 2022.

It’s certainly true that board game sales in recent years have seen an upwards trend, and one set to continue, with the global board games market projected to hit just over 40 billion US dollars by 2029. If like me, you lack the appropriate financial knowledge to interpret that number, this puts board games in more or less the same economic league as shampoo (40 billion USD by 2028), but in a lower division than, say, bananas (146 billion USD by 2029).1

Their popularity may wax and wane, but the history of board games reaches as far back as the earliest human civilisations. From ancient Mesopotamia, for instance, we have The Royal Game of Ur, so named after a set of wooden game boards which turned up in the 1920s at the Royal Cemetery in the once important city-state of Ur (in today’s Iraq). Somewhat familiarly, two players compete to be the first to get across the board with the help of some dice — we only know the rules thanks to the dogged determination of the British Museum’s Irving Finkel, who deciphered them from a Babylonian cuneiform clay tablet in the 1980s.

So, too, other ancient civilisations had their board games. For the Egyptians, there was Senet (another racing-across-a-board affair) and Mehen (rules yet unknown), the Romans had Ludus latrunculorum (of which more later), while in ancient China there was of course Go, and in ancient India Chaturanga (a likely forerunner of Chess).

Historically, these games travelled across land and sea with the people who played them, new cultures and communities encountering them along the way, and in the case of the Viking expansion in northwestern Europe, things were no different.

At the heart of the Norse game of Hnefatafl, a king and his retinue try to avoid capture by an opposing player’s forces who outnumber the king’s men by a ratio of 2:1 — a reflection that battle, in real life, is rarely fought on equal terms. (Hnefatafl likely drew on the model of the Roman Ludus latrunculorum, another strategic capture game, with the asymmetric configuration as a Scandinavian innovation.)2

Traces of Hnefatafl in the Viking world are both textual and material, and indicate that, far from being solely for children’s entertainment — often associated with board games today — this was the pursuit of ambitious kings and fearsome warriors.

In Morkinskinna, a history of Norwegian kings from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the game is cited in a verbal contest between two brothers, King Sigurðr and King Eysteinn, the latter arguing that his skills on the Hnefatafl board are as worthy as the physical prowess of his brother:

King Sigurðr said: “I believe, King Eysteinn, that I am stronger and a better swimmer.”

“That is true,” said King Eysteinn, “but I am more skilled and better at hnefatafl, and that is worth as much as your strength.”3

The Hnefatafl board was indeed an important arena in which to hone one’s strategic acumen. In Frithiof’s Saga, the title hero, whilst playing the game himself, offers advice to his foster-father Hilding in relation to a battle against an enigmatic King Ring, counselling that “the Hnefi [= the game’s king-piece] should be attacked first”.

As high-status objects, board games made for appropriate royal gifts in a culture where strategic generosity was critical in the pursuit of good social standing. Another saga, the Saga of Refr the Sly, features a gaming board fashioned out of walrus ivory by a Greenlander and offered as a gift to King Harald Hardrada of Norway, in return for friendship. According to the saga, the board could be used for Hnefatafl as well as chess (Skáktafl), which at this point had arrived in Scandinavia, and ultimately supplanted Hnefatafl in later years.4

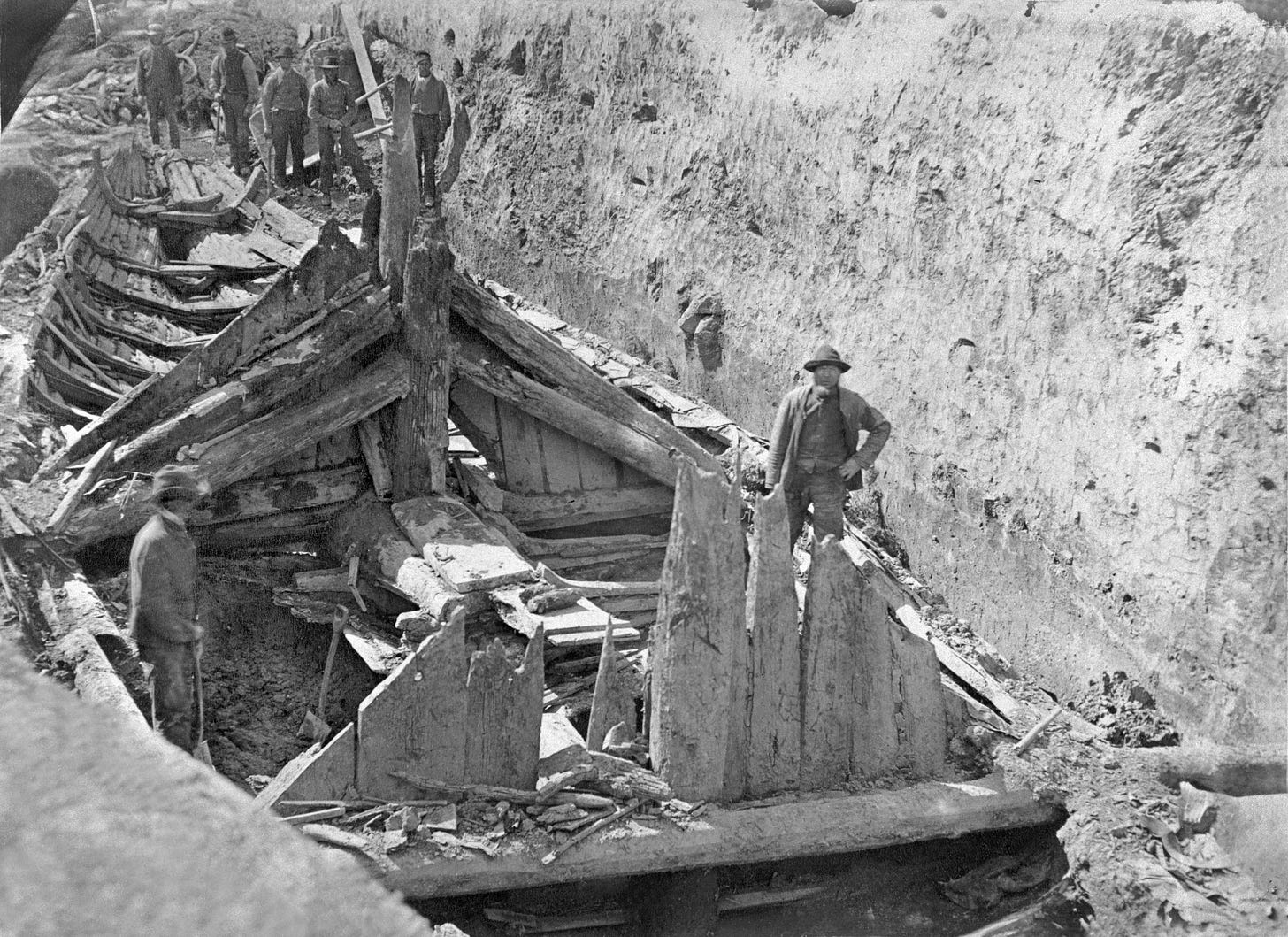

These textual references to Hnefatafl are complemented by archaeological finds which indicate that, in death as in life, board games were associated with adults of high social status. Gaming pieces and boards turn up in prestigious Viking burial graves, such as in the well-known Gokstad ship burial from c. 900 CE, discovered in the late nineteenth century by two Norwegian farmer’s sons. The gaming materials were found along with the remains of 64 shields, 12 horses, eight dogs, six beds and two peacocks, not to mention the boat itself, clinker-built and of skilled craftsmanship.

Similar game-related finds in parts of the Viking diaspora testify to the transmission of Hnefatafl across the sea. Gaming pieces and boards have been uncovered across the British Isles, most recently an exquisite glass gaming piece with a crown of five white droplets on the Northumberland island of Lindisfarne (synonymous with the early Viking raid of 793), and a complete set of 37 lead pieces in Lincolnshire, discovered by a retired miner, now metal-detector hobbyist (the set subsequently sold for £3,224 at auction).

It has even been suggested that the famous Lewis chessmen from the Outer Hebrides may too have been used to play Hneftafl, in keeping with the multi-functionality of gaming equipment indicated in the sagas with the dual-use Greenlandic board.5 (I am reminded of the travel games compendium I had as a child, a recipe for unending fun on a long journey — chess, draughts, backgammon and ludo, all in one!)

We should bear in mind that games in the age of the Vikings — as throughout pre-modern history — were not so much fixed objects with set rules, as in today’s commercial offerings, but naturally evolved over time and space, much like folk tales and ballads.6 Hnefatafl, as it was played across the Viking world, is thus best thought of as a family of games, variations on a central, escaping-against-the odds theme.

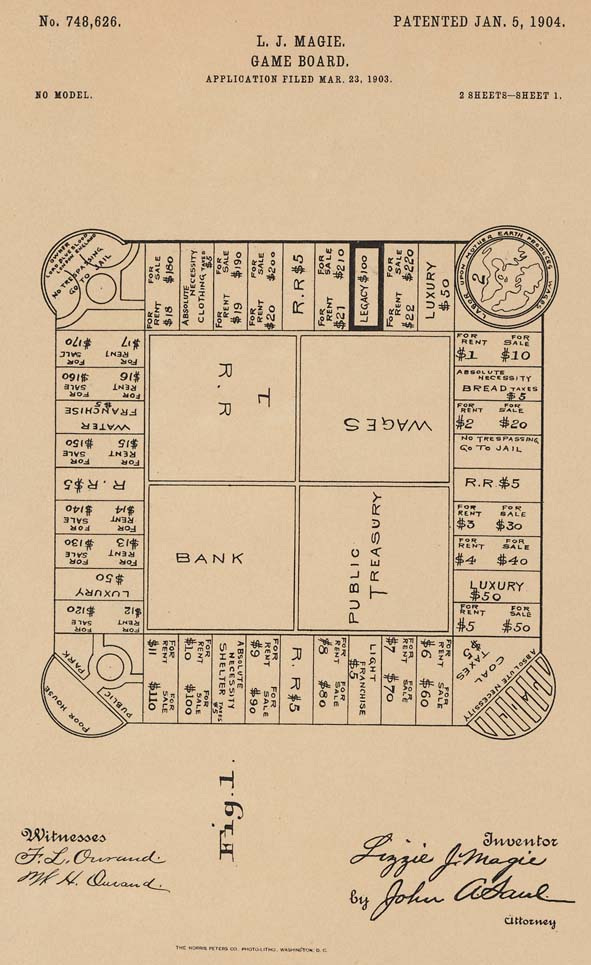

Indeed, perhaps the strength of the board game is precisely this adaptability; they can be moulded to suit the hopes and fears of those who play them. Think, for example, of the emergence of Monopoly and its imitation of unleashed capitalism in the early twentieth century. (In fact, in the original conception of the game, there were two sets of rules, one which favoured monopolies and the crushing of opponents, and one which centred on overall wealth creation, rewarding all players when someone acquired a new property. Somewhat predictably, the pro-monopolist rules won out in the end.)

Today’s board game trends in many ways reflect the prevailing winds in our own culture. Games that emphasise teamwork and collaboration over competition are emerging in increasing numbers, presumably connected to the “every-one’s-a winner” philosophy which now has a foothold in schools and beyond. Single-player games are also on the rise, an inevitable market winner in our socially atomised culture.

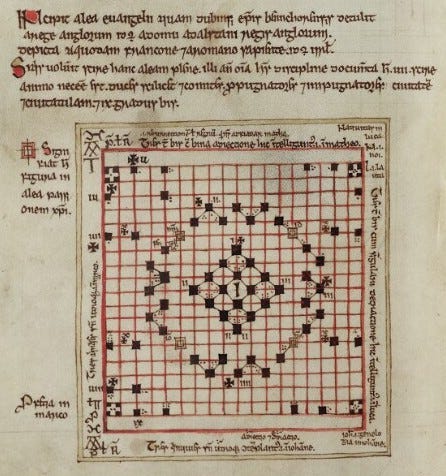

The medieval Hnefatafl variations similarly reflected their societal surroundings. A good example here is an Anglo-Saxon variant. Labelled in one manuscript as Alea Evangelii (“Game of the Gospel”), this was Hnefatafl through a Christian lens. Appropriately for the tenth-century court of the pious King Æthelstan at which it was apparently known, in this version Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were each assigned a side of the board, while the primary piece at the centre was said to represent the Holy Trinity.7

Nineteenth-century revivals of the Hnefatafl family appear to have kept up this tradition of adapting to the surroundings. In 1855, a game by the name of Imperial Conquest appeared in London mirroring the factions of the unfolding Crimean War, where the Russian emperor and his eight defenders had to escape from sixteen attackers representing allied Britain, France, Turkey and Sardinia. A later incarnation, Freedom’s Contest, appeared in 1863 during the American Civil War, where a rebel chief and defending Confederate soldiers attempted to escape from Union defenders.8

To know the board games a society plays, it seems, is to know a good deal about that society’s priorities and preoccupations.

https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2024/10/08/2959818/28124/en/Board-Games-Market-Insights-2024-2029-with-Asmodee-Hasbro-Mattel-and-Ravensburger-Dominating-the-41-07-Billion-Market.html; https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/shampoo-market; https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/banana-market

Mark A. Hall & Katherine Forsyth, Roman rules? The introduction of board games to Britain and Ireland. Antiquity 85(330), 2011, pp. 1325-1338.

Adapted from: Theodore Murdock Andersson & Kari Ellen Gade (trans.), Morkinskinna: The Earliest Icelandic Chronicle of the Norwegian Kings (1030-1157). (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000), p. 346. For the corresponding Old Norse, where the board game is explicitly named as hnefatafl, see this entry in the Dictionary of Old Norse Prose.

David H. Caldwell, Mark A. Hall & Caroline M. Wilkinson, The Lewis hoard of gaming pieces: a re-examination of their context, meanings, discovery and manufacture. Medieval Archaeology 53(1), 2009, pp. 155-203.

David H. Caldwell, Mark A. Hall & Caroline M. Wilkinson, The Lewis hoard of gaming pieces: a re-examination of their context, meanings, discovery and manufacture. Medieval Archaeology 53(1), 2009, pp. 155-203.

Tristan Donovan, The four board game eras: making sense of board gaming’s past. Catalan Journal of Communication & Cultural Studies 10(2), 208, pp. 265-270.

J. Armitage Robinson, The Times of St. Dunstan (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1923), pp. 69-71, 171-181.

Very interesting, thank you. As you'll doubtless know there's also tabula

https://www.mastersofgames.com/rules/tabula-rules.htm