On the margins

Changing perspectives on land versus sea

Striking news from the east. I read that sea levels in the Baltic are at such an historic low that the situation may trigger a large inflow of water from its saltier neighbour, the North Sea. It’s a reminder that the small patch of Europe where my attention tends to rest is connected to a wider whole — a marginal sea in the grand scheme of things, and yet at the heart of nearly all things that mean the most to me.

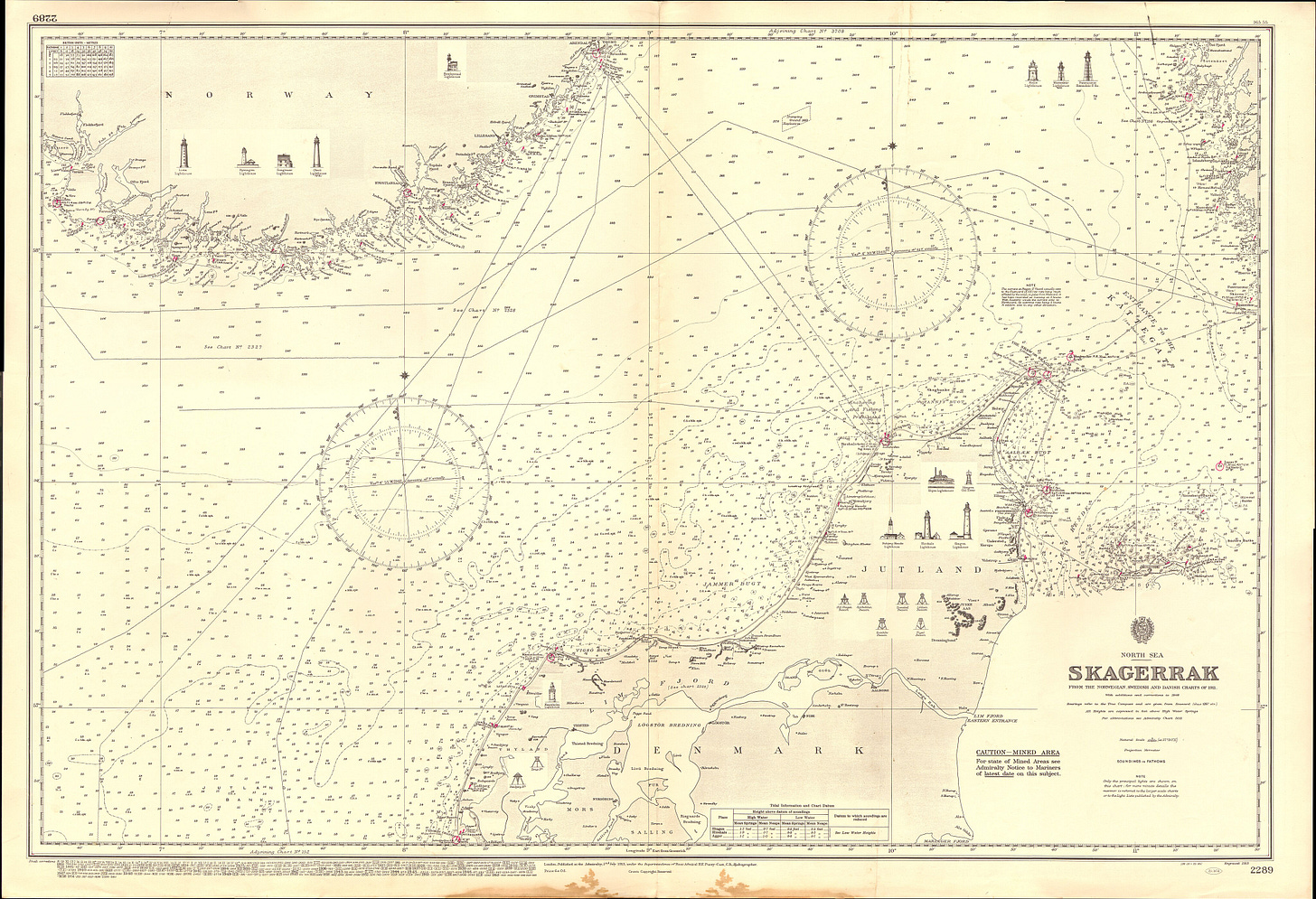

If such an inflow occurs, it will run east via the Skagerrak, the North Sea’s stubby right arm. It’s funny to think of a sea having arms, not least since this variety rarely come in pairs of equal size. As a shore-dweller who travels more frequently by air than water, I’m prone to thinking instead of the land extending out into the sea — headlands, nesses, tongues, spits. Though, at a different time and in a different life, I can imagine how the reverse perspective — eyes seeking bays, inlets, arms — could creep in.

In fact, it strikes me now that I have long been living in the shadows of such sea-heavy lives and times, almost without realising — hours spent amongst terse Norse sagas and dry Low German charters from the golden age of the Hanseatic League. And now my time is happily split between the Netherlands, North-East England and Genoa, erstwhile maritime heavyweights navigating new and somewhat tricky futures in their own ways.

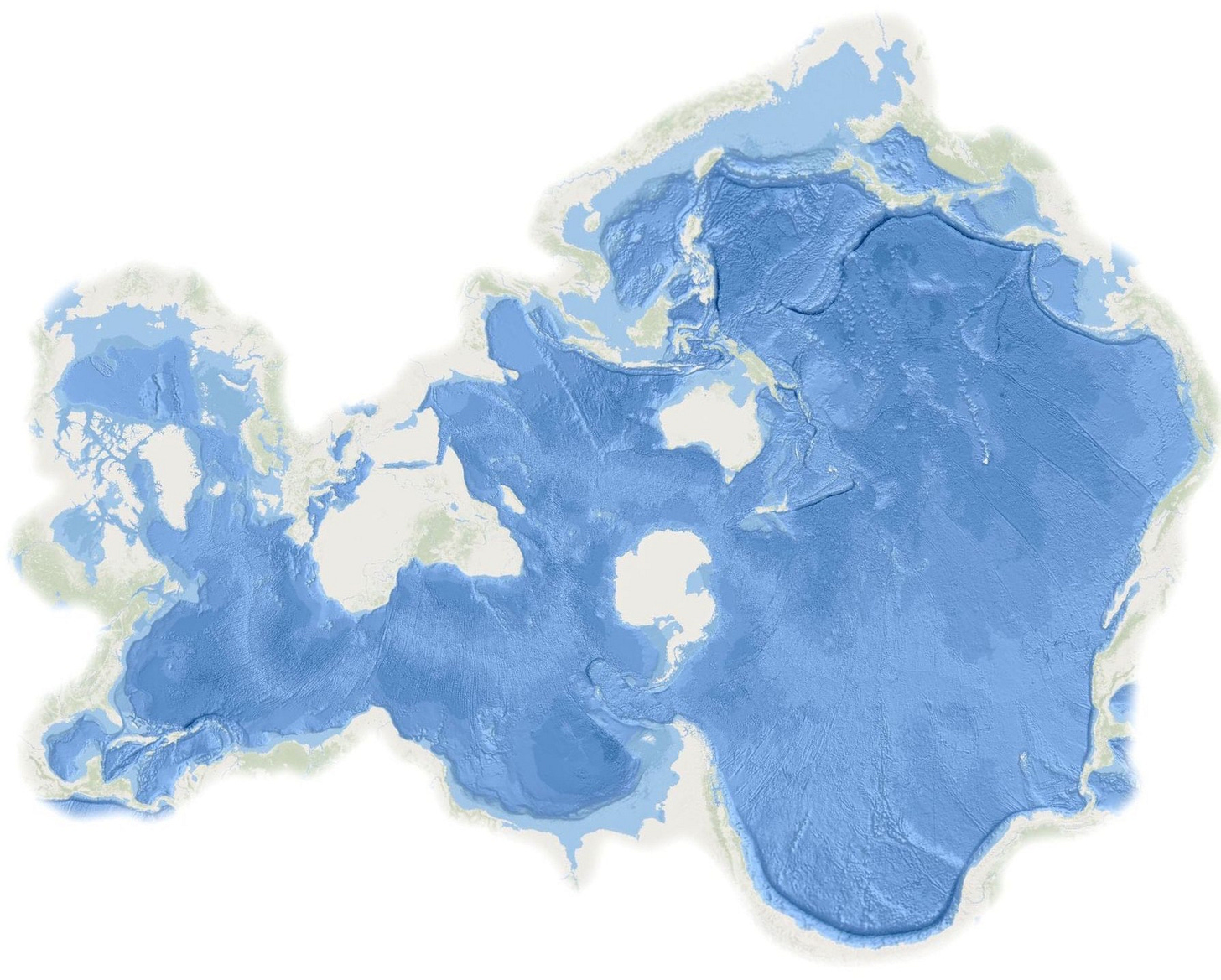

Still, even with these regular reminders, the sea-before-land perspective is for me, like many others, hard to fully grasp. At least without the jolt of a visual twist. One such twist recently went on display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich — an ocean-centric map based on the Spilhaus cartographic projection. Here, the world’s oceans and seas show up as a mass of mottled blues bounded by ghostly, seemingly incidental coastlines and continents. Named after its creator, Cape Town-born oceanographer Athelstan Spilhaus (1911-1998), Spilhaus is certainly an appropriate label for it. The world’s waters spill out across the map into any bay, gulf or arm they can find.

Viewed this way, the North Sea is a shallow pocket tucked away at one end of the Atlantic. Small though it is, it is enticingly open at one end — perhaps dangerously so. Meanwhile, its mismatched arms or sleeves — the Skagerrak and the Channel — are strikingly slim. No wonder they each host some of the busiest shipping routes in the world.

To see the oceans, slice up the land — this was the mantra of Spilhaus when he came up with the idea of a map ‘interrupted within the land masses’.1 His mind may have been on ocean currents and other sea-bound phenomena but, as always, a better understanding of the world around us only gives greater perspective on our narrow place within it.

Some snatches from my travels through sea-heavy lives and times:

The ring of the world, which mankind inhabits, is deeply scored by bays; large bodies of water run from the ocean into the land

— opening to Ynglinga saga (Heimskringa), Old Norse-Icelandic, early 13th century2

~

Alle kleine water lopen in de groten [All small waters run into great ones]

— Low German proverb, early 16th century3

~

They told me last night there were ships in the offing,

And I hurried down to the deep rolling sea

— Blow the Wind Southerly, Northumbrian folk song, early 19th century

Athelstan Spilhaus, To See the Oceans, Slice Up the Land. Smithsonian 10, 1979 pp. 116-122.

Athelstan Spilhaus, Maps of the whole world ocean. Geographical Review 32(3), 1942, pp. 431–435.

In the Old Norse-Icelandic (p. 4): Kringla heimsins, sú er mannfólkit byggvir, er mjǫk vágskorin; ganga hǫf stór ór útsjánum inn í jǫrðina

From: Die älteste niederdeutsche Sprichwörtersammlung von Antonius Tunnicius (Berlin, 1870), no. 63, p. 21.

I like this change of perspective. Thank you for the information and point of view.

I had seen the Spilhaus map before, but never quite considered that image of the North Sea with two outstretched arms. But why is the Baltic losing water? Something to do with the freshwater inputs?