The search for Doggerland

An unlikely alliance between fishermen, oil companies and archaeologists

In September, 1931, Skipper Pilgrim E. Lockwood, Master of the Sailing Trawler Colinda, […] was fishing at night between the Leman and Ower. He hauled his trawl and landed a large mass of “Moorlog” a local name given to lumps of black wood and peat which are found in this situation and elsewhere in the North Sea. […] Instead of heaving it over, Skipper Lockwood broke it up with a shovel which hit something hard. In his own words (which I wrote down verbatim) on the 14th of March, 1932 he says:

— “I hear the shovel strike something. I thought it was steel. I bent down and took it below. It lay in the middle of the log which was about 4 feet square by 3 feet deep. I wiped it clean and saw an object quite black.”

He realised he had found something of unusual interest.1

The Colinda and its crew, based at Lowestoft on the Suffolk coast, had been fishing about 25 miles into the southern North Sea, between the Leman and Ower sandbanks, when the chance discovery was made. It was to change our historical understanding of the North Sea forever. For the object hidden within the “moorlog” turned out to be a prehistoric barbed antler point, from a time when the southern North “Sea” was dry and our early ancestors roamed across a vast plain connecting what we today know as England and the Netherlands.

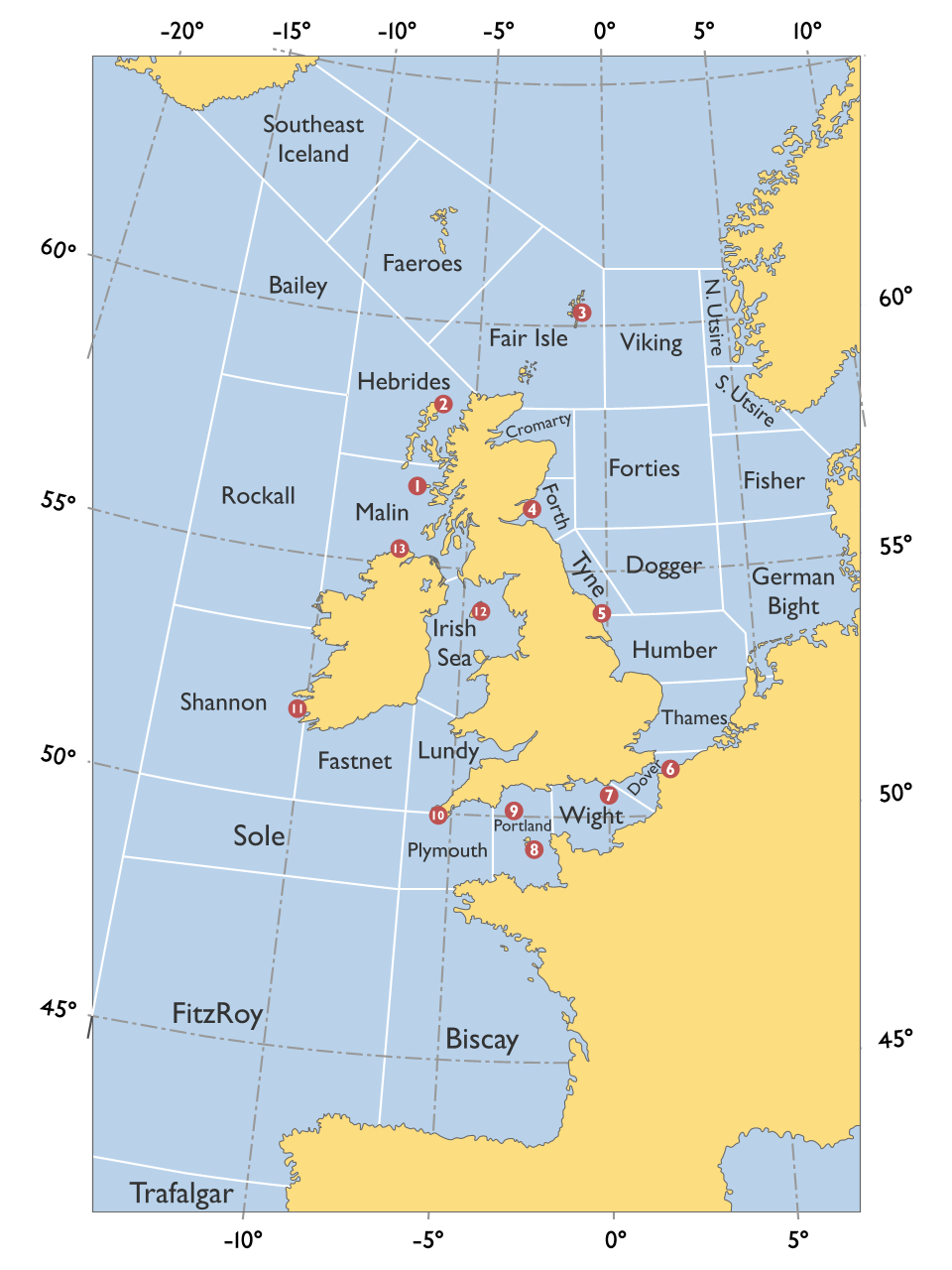

This submerged land has come to be known as Doggerland, after another of the many underwater sandbanks or “shoals” which pepper this part of the North Sea bed. For British readers, this is the same Dogger that likely triggers echoes of that famous cultural institution, the Shipping Forecast, where Dogger comes sandwiched between (the admittedly somewhat prosaic) Tyne and the ever evocative German Bight.

In fact, rumours of a lost land in this part of the North Sea had been quietly spreading for some years by the time of the Colinda find. For many decades, dredgers and trawlers working in the area had brought up bones of various land animals: bears, bison, mammoths, elk.

Mysterious tree stumps visible at low tide on North Sea coasts also hinted at a drowned land stretching out to sea. These “submerged forests” had previously caught the eye of British geologist Clement Reid who, himself calling on accounts of fishermen, noted in 1913:

…the fishermen will tell you of black peaty earth, with hazel-nuts, and often with tree-stumps still rooted in the soil, seen between tide-marks when the overlying sea-sand has been cleared away by some storm or unusually persistent wind. If one is fortunate enough to be on the spot when such a patch is uncovered this “submerged forest” is found to extend right down to the level of the lowest tides.2

After painstaking analysis of plant remnants in the moorlog from Dogger Bank — a rather messy business which Reid conducted with his wife, apparently involving boiling the peaty mixture in a strong soda solution for three or four days — the results indicated a location in “the middle of some vast fen”, there being “little sign of brackish-water plants, or even of plants which usually occur within reach of an occasional tide”.3

And so the idea of a great plain stretching across the southern North Sea, a land bridge between England and the Netherlands, was now in play. The Colinda antler some eighteen years later marked another giant step: here was robust physical evidence of human activity in this lost land, direct from the sea floor. (Sadly Reid didn’t live to see the Colinda find, having died in 1916.)

Methods available at the time dated the Colinda find, likely used as a fish spear, to the Mesolithic period or “Middle Stone Age” (around 10,000 to 4,000 BC in Britain), while more recent investigation points to the 12th century BC (Late Paleolithic).4 Crucially, a time when enough water was still locked away in glaciers and ice sheets from the last Ice Age, and had not yet melted and flooded Doggerland, cutting Britain off from the European Continent — a point which is assumed to have been reached around 6500 BC.

These early clues in the modern search for Doggerland speak for an unlikely alliance between fishermen and archaeologists which continues to be fruitful to this day, regularly yielding finds of scientific interest.

Other, similarly unlikely partnerships have formed through this quest. Since — even by today’s standards — doing archaeology on the sea bed is tricky, academics have teamed up with oil companies and their seismic surveys, originally conducted for petroleum exploration, to research the lost landscape.

Strikingly, many Doggerland finds in recent decades have been found on the beaches of South Holland, where the coast is regularly reinforced by sand replenishments dredged up from the North Sea bed. So frequent are prehistoric finds on one of these beaches, the Maasvlakte, that Port of Rotterdam have set up a dedicated “Finds Checker” for members of the public to report their discoveries and get feedback from experts. Titles of recent submissions include the descriptive (“very hairy bone”) and the humble (“no idea what it is”).

As the Dutch battle the loss of today’s land to the sea, they are simultaneously revealing a lost culture that, many thousand of years ago, suffered that very same fate.

H. Muir Evans, H. Godwin, M. E. Godwin, H. M. E., J. Reid Moir & M. C. Burkitt. (1932). East Anglian Notes. In Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia, 7(1), 131–133.

Reid, C. (1913). Submerged Forests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reid, C. (1913). Submerged Forests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bailey, G. et al. (2020). Great Britain: The Intertidal and Underwater Archaeology of Britain’s Submerged Landscapes. In: Bailey, G., Galanidou, N., Peeters, H., Jöns, H., Mennenga, M. (eds) The Archaeology of Europe’s Drowned Landscapes, 189–219. Cham: Springer.