I recently spent three years living in Flanders, in the city of Ghent to be precise, which sits between Bruges and Brussels and, in my opinion, gets unfairly squeezed out of too many tourist itineraries by its better-known neighbours.

Little did I know that, as an English woman arriving in this part of the Low Countries — under the pull of a Flemish university and a very generous research grant — I was following in the footsteps of many who had gone before me.

I was lucky, however. My arrival in Flanders in 2021 was by choice — not so for many of those who came before me.

Some weeks ago, I wrote about the flow of English Catholics into Flanders — one Guy Fawkes included — amidst the religious upheavals of Elizabethan England. But this was far from the first time that Flanders played host to those who had fallen out of favour in the land across the sea.

Earlier, in eleventh-century England, as Danish and Norman invasions sparked a febrile atmosphere and fierce competition for power among the elite of Anglo-Saxon society, the low-lying principality just over the horizon offered a place of refuge for those down on their luck in these turbulent times.

Particularly precarious were royal women, whose stars rose and fell with the shifting fortunes of their male kin. When times were good, these women could enjoy some authority at court, by way of marriage or blood. When times were bad, such as following the death of a king, this authority could quickly become a liability, a lightning rod for dissenting factions and political machinations and, in the eyes of a successor to the throne, a risk too high to tolerate close to home.

So it was that Emma of Normandy was exiled following the death of her husband King Cnut in 1035 and the chaos which ensued. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle informs us that Emma, who by now had been twice Queen of England by marriage, ‘was driven out without any mercy to face the raging winter’.1 It was, unfortunately for Emma, not the first time that this had happened. Two decades earlier, in 1013, she had fled to her native Normandy for a year or so, when the fortunes of her first husband, King Æthelred the Unready, had taken a turn for the worse following the invasion of England by the Danish King Sweyn Forkbeard.

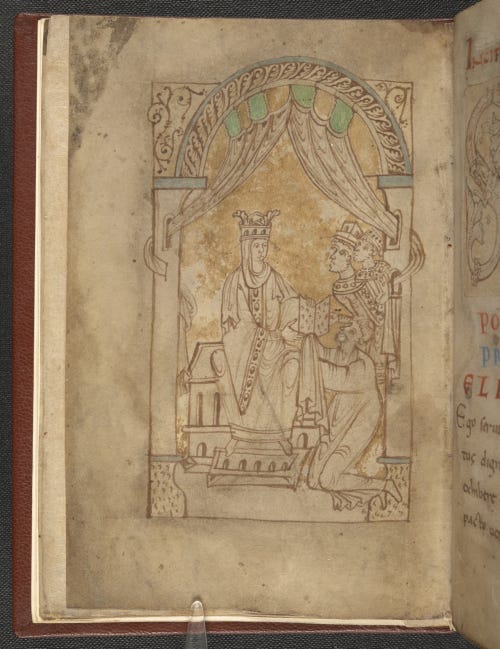

Now a widowed queen for the second time, Emma again found herself driven out across the sea, this time to Flanders. As the Encomium Emmae Reginae, later written at her request by most likely a Flemish monk, puts it:

And so, having enjoyed favourable winds, they crossed the sea and touched at a certain port not far from the town of Bruges. The latter town is inhabited by Flemish settlers, and enjoys very great fame for the number of its merchants and for its affluence in all things upon which mankind places the greatest value.2

Like my own stay in Flanders, Emma remained just three years in Bruges, until 1040, when she returned to England to see her son by Cnut, Harthacnut, become King of England. From her adopted residence in Bruges, generously provided by Baldwin V, then Count of Flanders, Emma had been a key champion for Harthacnut and his right to the English throne — indeed, this was likely a key motivation for her commissioning of the Encomium Emmae Reginae in the first place.

During her time at the Flemish court, Emma and her impressive example of what queenly sway could achieve — even from afar — likely influenced Baldwin’s daughter, the young Matilda of Flanders, who would later marry a certain William of Normandy and herself become Queen of England, following yet another grand turn of events in eleventh-century England.3

Indeed, fast forward a few years to 1067 and Matilda, now married to a recently crowned William I, arrives in England just as the next wave of Anglo-Saxon elites are fleeing for Flanders in the wake of the Norman conquest — among them the female kin of the late Harold Godwinson.4 With Matilda’s coming and the Godwinson’s leaving, the changing face of England’s elite played out on the short stretch of sea between England and its closest neighbours.

We know that this latest wave of exiles included, along with Harold’s mother Gytha, his younger sister Gunhild, whose tomb was discovered in 1786 in the walls of the comital chapel at Bruges. Buried with her was a plaque stating that Gunhild ‘fled her homeland and lived for some years in exile at Saint-Omer in Flanders’ (now in the Pas-de-Calais of modern-day France).5

Unlike Emma (and indeed myself), Gunhild’s temporary stay in Flanders became permanent, and the plaque, still held in Bruges, now in the treasury of St Salvator’s Cathedral, reminds us of the risks of being a medieval woman too close to a king.

Daniel Anzelark, Life, letters and exile in Early Medieval England. Neophilologus 107, 2023, pp. 85-101.

Alistair Campbell (ed.), Ecomium Emmae Reginae (London: Royal Historical Society, 1949), p. 47.

Tracy Borman, Matilda: wife of the Conqueror, first Queen of England (London: Jonathan Cape, 2011).

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 1067 (version D):

This year went out Githa, Harold's mother, and the wives of many good men with her, to the Flat-Holm, and there abode some time; and so departed thence over sea to St. Omer's. This Easter came the king to Winchester; and Easter was then on the tenth before the calends of April. Soon after this came the Lady Matilda hither to this land; and Archbishop Eldred hallowed her to queen at Westminster on Whit Sunday.

Elisabeth van Houts, King Harold’s Sister Gunhild (d. 1087), a royal exile in Flanders. The English Historical Review 138(590-591), 2023, pp. 1–26.