An intriguing news story from Belgium recently caught my eye. It concerns an old shipwreck, some twenty miles off the Flemish coast near Ostend. And yet, this is a tale of life rather than loss.

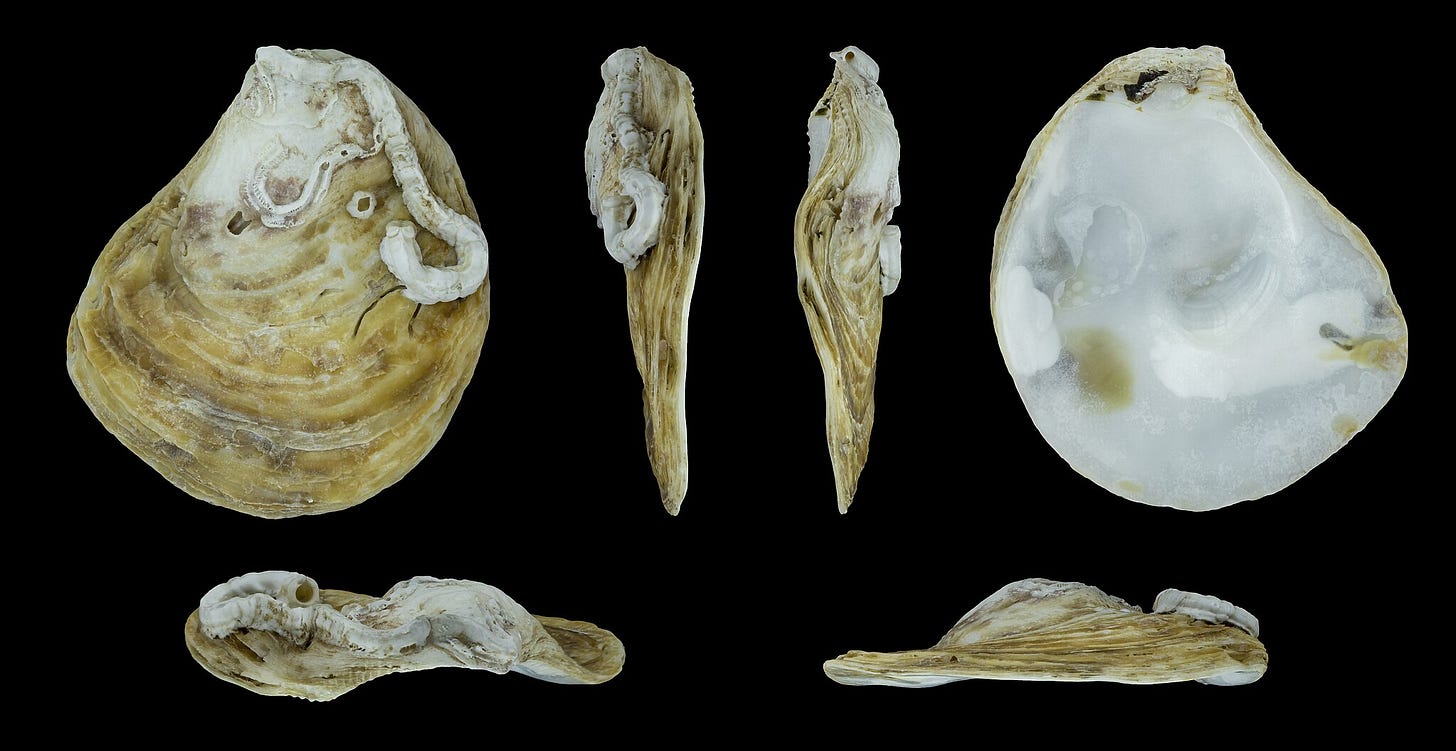

The wreck of the Kilmore — a British cargo vessel which sank en route from Antwerp to Liverpool in 1906 — is the site of an ambitious ecological experiment this summer. Automatically protected as underwater cultural heritage, and thus off-limits for fishing vessels and other forms of human intervention, it is a perfect place to trial the restoration of a native though now critically endangered North Sea dweller: Ostrea edulis, or the European flat oyster.

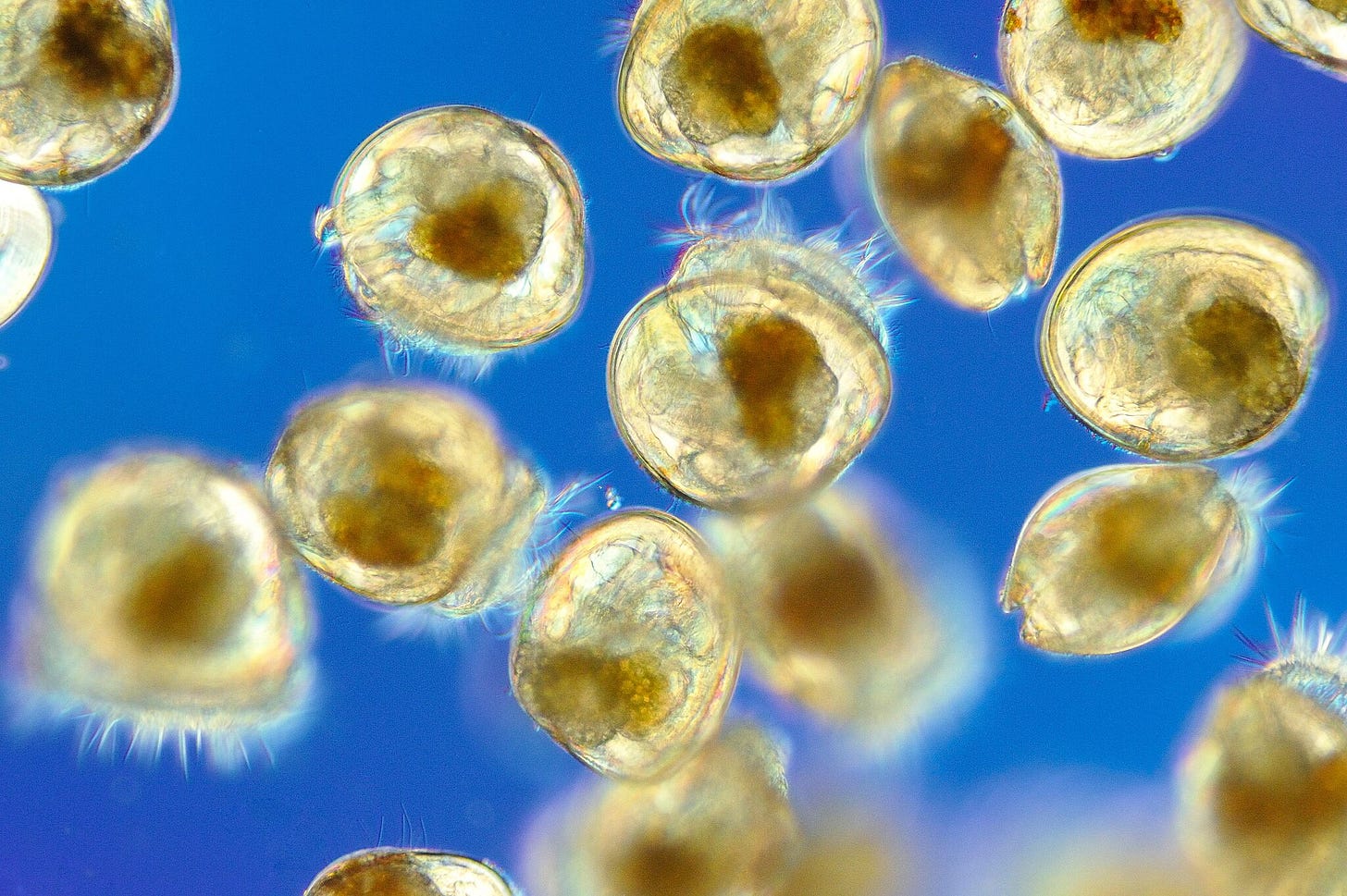

Not only is the site safely shielded from potentially disruptive human activities (many of which led to the demise of North Sea oysters in the first place); the wreck itself offers a sheltered habitat in which new life can grow and thrive, or so is hoped. 200,000 oyster larvae were recently deposited in what remains of the Kilmore’s hull as part of the BELREEFS project — a small step towards restoring the rich oyster reefs that once dominated the Belgian North Sea. The hope is that, from here, the transplanted bivalves will soon start reproducing, in time creating a self-sustaining reef which will stabilise the seabed, provide homes and feeding grounds for fellow marine species, all the while purifying the water through a natural filtration process. It’s no wonder oysters have come to be known as ‘ecological engineers’ in the academic literature.

The Kilmore herself dates from a time when oyster reefs were much more abundant in the North Sea. Launched on the Tyne in 1889, in an age when Tyneside’s shipyards, much like the oysters out at sea, were still rich and plentiful, the Kilmore was fitted with ‘all the latest improvements for the rapid handling of cargo’.1 These had been put to good use to load the continental porcelain, glass and copper bolts bound for Liverpool in July 1906.

The cargo, however, would never make it beyond the Flemish coast. In the early morning of July 29th, the Kilmore collided with the steamship Montezuma. Reports are that there was a misunderstanding as to which side of a local lightship each vessel would pass.2 What was intended as a helpful navigational aid in hazardous waters had unfortunately served the opposite effect. The Kilmore came off worse, though luckily all of her crew were rescued by the Montezuma. The Kilmore herself sank, coming to rest on the seabed atop some old gravel beds that once hosted natural oyster reefs — a hint of things to come over a hundred years later.

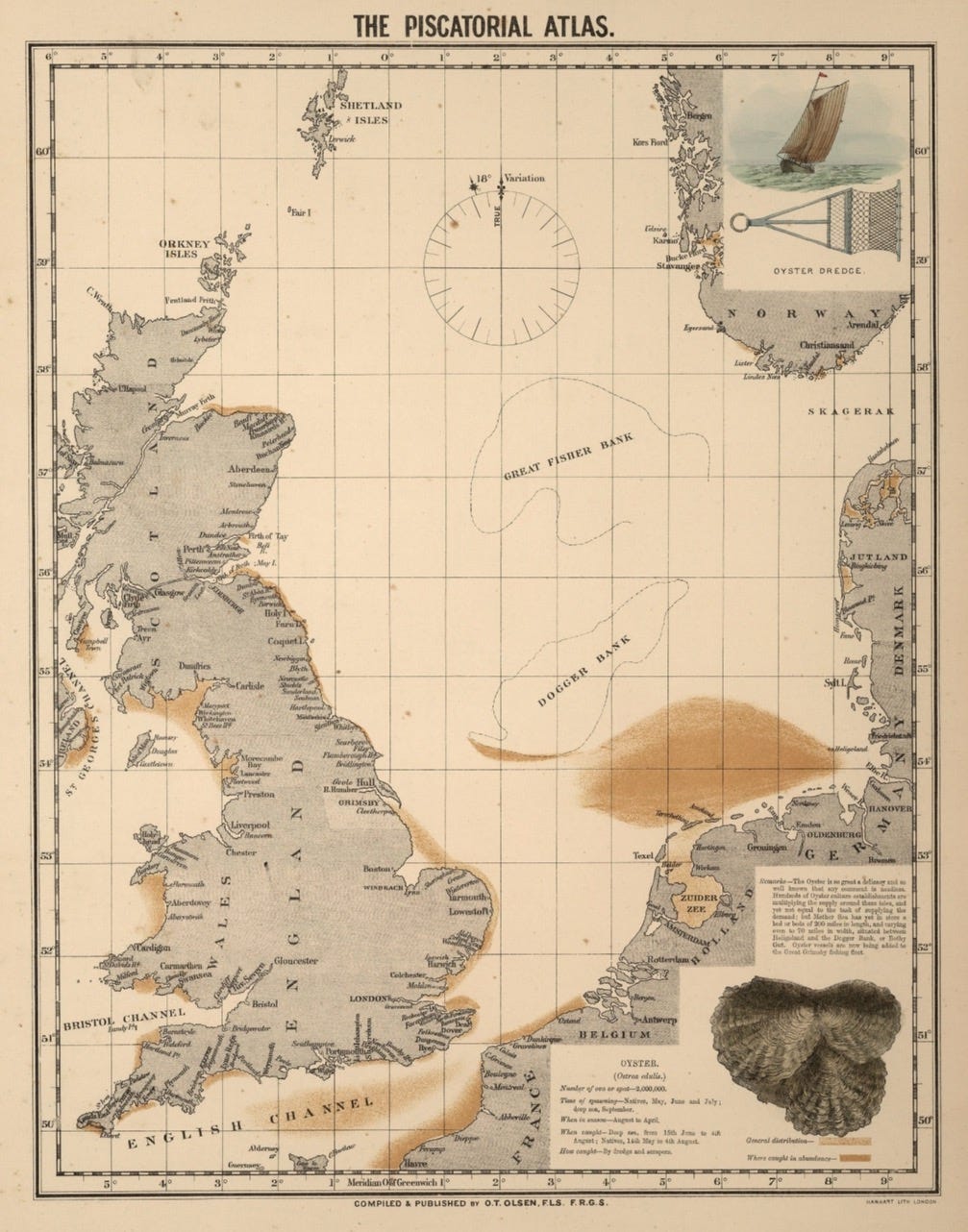

Of course, in the Kilmore’s time, oysters were far from the luxury product they are today. Like so many of our most sought-after shellfish — mussels, clams and lobsters — oysters too were humble staples not so long ago. Official figures for 1886, just three years before the Kilmore’s launch on the Tyne, record the number of British oysters produced that year at forty million — a bountiful source of protein for working-class communities growing in number.3 As Charles Dickens’ character Sam Weller remarks in The Pickwick Papers, in Victorian Britain ‘the poorer a place is, the greater call there seems to be for oysters’, whether as a cheap filler in beef & oyster pie, or a ready and affordable bar snack served with beer.4

But with scarcity comes exclusivity and, as the North Sea’s native oyster stocks suffered overfishing, pollution and disease, so the increasingly precious bivalves became the preserve of the wealthy. Since the mid-twentieth century, Ostrea edulis has been considered ‘functionally extinct’ in the Southern North Sea, that is, more than 99% lost.5 Even at the celebrated Whitstable Oyster Festival on the north Kent coast, the festival fare these days mostly comprises imported and easier-to-cultivate Pacific species, rather than the native oysters of the Kentish flats prized and sought after since Roman times.6

But, as with the Belgian shipwreck experiment, fresh hope for the European flat oyster can be found in surprising places. A recent feasibility study in Scotland showed that offshore wind farms — like shipwreck sites, protected and thus disturbance-free — offer another opportunity for large-scale native oyster reef restoration.

Perhaps one day, Ostrea edulis will once more be affordable for all.

Shields Daily Gazette, 27/11/1889.

Lloyd's List, 05/11/1906.

Robert Neild, The English, the French and the oyster. (London: Quiller Press, 1995). As cited in: John Humphreys, Roger J. H. Herbert, Caroline Roberts & Stephen Fletcher, A reappraisal of the history and economics of the Pacific oyster in Britain. Aquaculture 428–429, 2014, pp. 117-124.

Charles Dickens, The Pickwick Papers (1836-37), Chapter 22, via Project Gutenberg.

Lasse Sander, H. Christian Hass, Rune Michaelis, Christopher Groß, Tanja Hausen, Bernadette Pogoda, The late Holocene demise of a sublittoral oyster bed in the North Sea. PLoS ONE 16(2), 2021, e0242208.

Phil Hubbard, ‘Trouble in Oysteropolis’: The contested geographies of aquaculture at the North Kent coast. Coastal Studies & Society 4(1), 2025, pp. 3-30.

Establishing oyster beds under windfarms is such a fantastic idea.

Another fascinating article, Hannah. So many wonderful links, planting new oyster beds in a shipwreck off Ostend, a meal in Charles Dicken's Pickwick Papers, the Whitstable Oyster festival with imported stock and a wonderful, historical map of previous oyster beds. Thank you.